11. Nuclear Power#

Quick Links

From the Reading List

Nuclear fission [Martin] Chapter 2.7, 8.1

Nuclear fusion [Martin] Chapter 8.2

Nuclear fission [Krane] Chapter 13

Nuclear fusion [Krane] Chapter 14

11.1. Introduction#

11.1.1. Basic energetics of nuclear power#

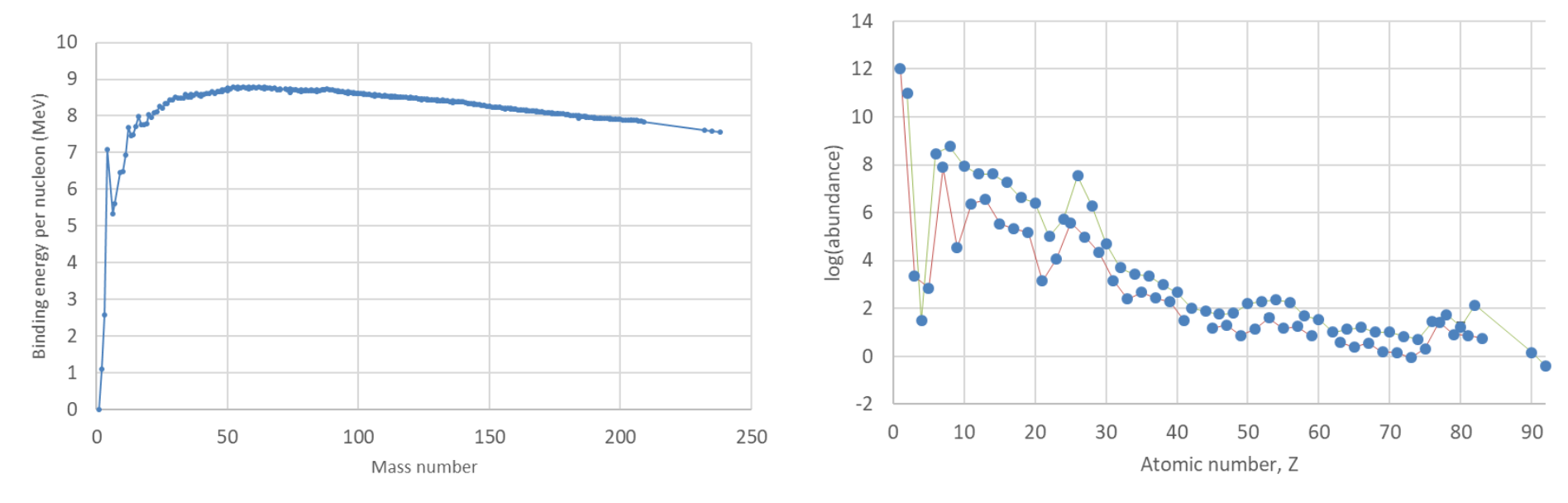

If we plot the binding energy per nucleon against the mass number (Figure 11.1), we find a broad maximum around iron. This implies that, in principle, it is energetically favourable for elements lighter than iron to fuse and for elements heavier than iron to split into smaller nuclei (by fission or, for nuclei not much heavier than iron, by \(α\) decay). If the elements formed in thermodynamic equilibrium, we would expect the elements around iron to be most abundant, but in nature the temperatures needed for this only occur in the interior of supernova explosions (producing a pronounced “iron peak” in the elemental abundances, see right panel of Figure 11.1).

Fig. 11.1 Left, binding energy per nucleon (MeV) against mass number A. (Data from Krane.) Right: solar system abundances, relative to hydrogen (set equal to 10\(^{12}\)). The lines join elements with even Z (green) and odd Z (red). The iron peak created by supernovae can be clearly seen. (Data from Lodders, ApJ 591 (2003) 1220, table 2.*)#

In fact, most of the elements up to bismuth \((Z = 83)\) have at least one stable isotope (the exceptions, which appear as missing points in the abundance plot, are technetium, \(Z = 43\), and promethium, \(Z = 61\)). The reason for this is the Coulomb barrier, which prevents light nuclei from getting close enough to fuse, and confines protons in heavy nuclei. Nevertheless, it remains the case that energy would be released by fission of heavy nuclei or by fusion of light nuclei. Stars are powered by nuclear fusion, although we have yet to surmount the technical challenges involved in achieving this on Earth (see the fusion section discussed later); on the other hand, we have solved the problems involved in generating energy by the fission of heavy nuclei.

11.2. Fission#

11.2.1. Physics of fission#

11.2.1.1. Spontaneous fission#

In the liquid drop model, a nucleus will decay by spontaneous fission if it is unstable to small changes in its shape. If we start with a spherical nucleus, a small elongation along one axis (pulling it into a rugby-ball shape, technically known as a prolate spheroid) will decrease the Coulomb term in the semi-empirical mass formula (the protons are a bit further apart) but increase the surface term (the surface area is increased). If we assume that the nucleons remain closely packed together, so that the volume stays the same, a small shape change of this type corresponds to changing the long axis to \(a=R(1+\epsilon)\) while reducing the short axes to \(b=R\sqrt{1+\epsilon}\), where \(\epsilon \ll 1\).

It turns out (Martin nor Krane proves this, so I’m not going to either!) that in this case

and

so

The nucleus will be unstable to spontaneous fission if this releases energy, so the condition from spontaneous fission is

(the exact number depends on the coefficients you adopt for the semi-empirical mass formula: Martin’s coefficients give 49, Krane’s give 47).

This condition is not met until well into the transuranic region, somewhere around \(A = 300\). However, it is an unduly pessimistic estimate, because it does not take into account quantum tunnelling: nuclei that have small fission barriers may be able to decay by spontaneous fission even though this does not look possible in the classical liquid drop model. In addition, some heavy nuclei are not spherical in the ground state, and we should also consider the effects of nuclear structure as described by the shell model. One effect of this is to make fission much more likely for even-even than for even-odd nuclei: for example, \(^{256}_{100}\textnormal{Fm}\) has a spontaneous fission half-life of 2.8 hours, whereas \(^{257}_{100}\textnormal{Fm}\) (which decays primarily by α emission) has a spontaneous fission half-life of 131 years. This appears to be related to the effect of the spin of the unpaired neutron. This feature is also seen in induced fission: neutron capture by \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\), producing the even-even nucleus \(^{236}\textnormal{U}\), is much more likely to induce fission than neutron capture by \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\).

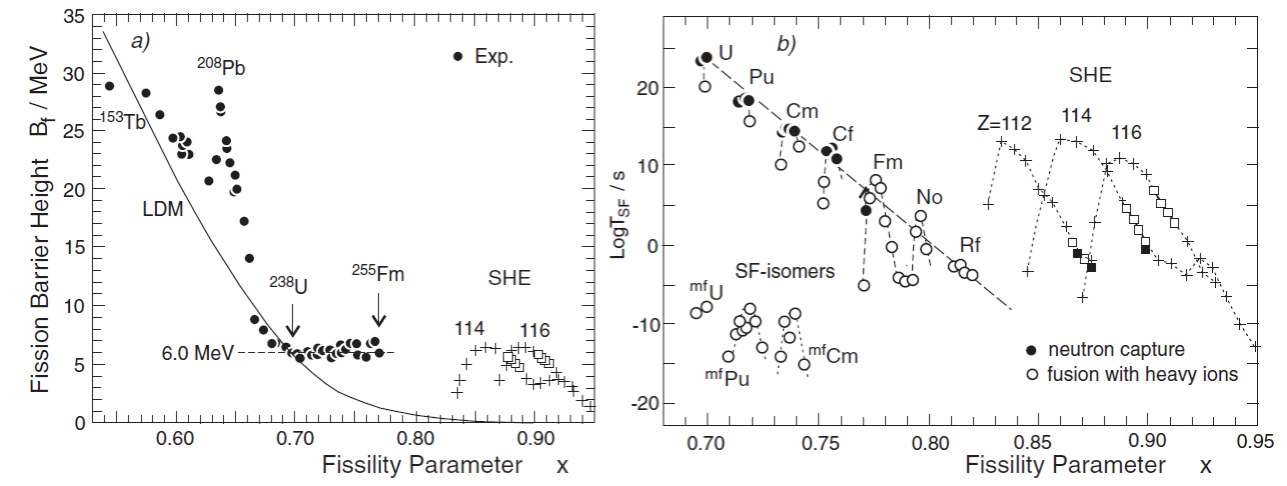

The effects of quantum tunnelling, non-spherical nuclei and shell corrections can be seen in Figure 11.2.Spontaneous fission becomes a viable decay mode for \( Z^2 / A \geq 0.75\left(Z^{2}/A\right)_{\text{crit}} \) (though it should be noted that the dominant decay mode for nearly all these very heavy nuclei remains α-decay).

Fig. 11.2 Spontaneous fission, plotted against fissility parameter (which in this paper is taken as 50.883). The left panel shows the height of the fission barrier, compared to the liquid drop model (LDM) prediction. Note that above uranium it settles down to around 6 MeV.The right panel shows the spontaneous fission half-life. “SF-isomers” are non-spherical excited states which have double-humped fission barriers, greatly increasing the tunnelling probability. The superheavy elements 112, 114 and 116 are predicted to be more stable against fission because of a neutron magic number at N = 162. Figure from Oganessian and Utyonkov, Rep. Prog. Phys. 78 (2015) 036301.#

11.2.1.2. Induced fission#

Even with the corrections for shell model effects and quantum tunnelling, it remains true that only very heavy nuclei decay by spontaneous fission. The heaviest naturally occurring isotope is \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\), and its half-life to spontaneous fission is \(8.4\times10^{15}\) years \((\)or, to put it another way, its branching fraction for spontaneous fission is \(5.4\times 10^{−5}~\%\)\()\). The only way to use fission to generate energy is to induce it by neutron capture. If the result of neutron capture is an excited state above the fission barrier, which as we can see from Figure 11.2 can be taken as 6 MeV for all relevant isotopes, then we have a good chance of inducing fission.

For example, the atomic mass of \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) is \(235.043924~u\). If we add a thermal neutron to this, we get \(236.052589~u\) (we can neglect the tiny kinetic energy of a thermal neutron). The atomic mass of the ground state of \(^{236}\textnormal{U}\) is \(236.045563~u\), so the level of excitation of the compound nucleus formed in the neutron capture is \(0.007026~u = 6.54~\textnormal{MeV}\). This is higher than the fission barrier, so this nucleus should decay by spontaneous fission.

In contrast, if we add a thermal neutron to \(^{23}\textnormal{U}\), the resulting \(^{239}\textnormal{U}\) has a mass only \(4.8 \textnormal{MeV}\) above the ground state mass. Even without the known suppression of spontaneous fission in even-odd isotopes, this is well below the fission barrier, explaining why neutrons with energies \(>1~\textnormal{MeV}\) are required to induce fission in \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\).

11.2.1.3. Characteristics of fission products#

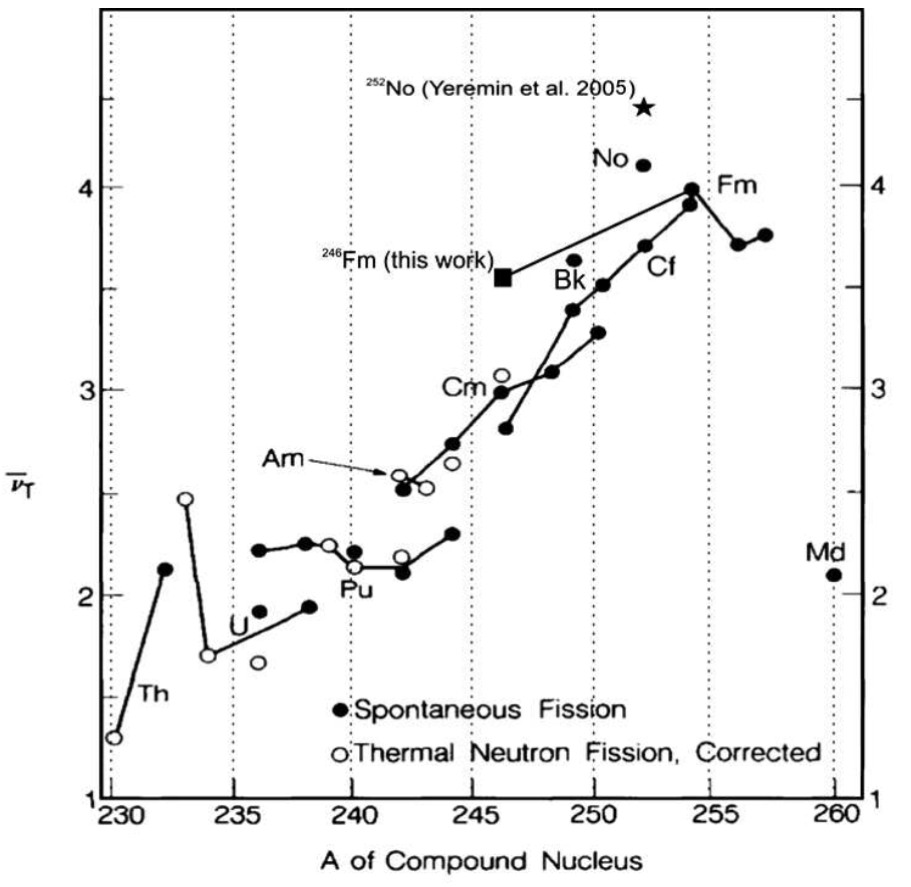

Fission generally produces two fission fragments, one with atomic mass around \(A=139\) and the other with whatever is left over (so the mass of the lighter fragment increases linearly with the mass of the fission parent), plus around 1–4 prompt neutrons. The mean number of neutrons increases with the mass of the parent, as shown in figure 11.3.

Fig. 11.3 neutron yield from fission. Note that nuclear physicists call this quantity ν̅: very unhelpful from a particle physicist’s perspective, since reactors also emit antineutrinos!From Svirikhin et al, Eur. Phys. J. A 44 (2010) 393.#

The reason for the near-constancy of the mass of the heavy fragment is that it is associated with the proton magic number 50 and neutron magic number 82. The fission process will naturally tend to produce fragments with magic numbers. The leftover mass is not close to any magic numbers, so it is the heavy fragment whose mass is constrained.

If a \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) nucleus fissions into fragments with masses 139 and 95 (allowing for the emission of two neutrons), and both fragments have the same neutron-to-proton ratio, the isotopes are \(^{95}_{37}\textnormal{Rb}\) and \(^{139}_{55}\textnormal{Cs}\). Neither of these is at all stable: the heaviest stable isotope of Rb is \(^{87}_{37}\textnormal{Rb}\), and the only stable Cs isotope is \(^{133}_{55}\textnormal{Cs}\). Therefore the fission will be followed by a cascade of β decays, as the fission fragments convert their excess neutrons to protons. In this particular case, the two decay chains are as follows:

In each case, the β decay also produces an electron and an antineutrino: thus this particular fission would produce an average of 6.8 antineutrinos. It would also produce an average of 0.087 delayed neutrons (delayed in this case by an average of 0.55 s, as the half-life of \(^{95}_{37}\textnormal{Rb}\) is 0.38 s). All the isotopes of rubidium with mass numbers between 92 and 102 have decay modes that involve the emission of a neutron, as do isotopes of strontium with mass numbers between 98 and 102 and several relevant isotopes of krypton. The consequence of this is that about 0.0162 delayed neutrons are emitted per fission of \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\). This has important implications for the control of fission reactors.

11.2.1.4. Energetics of fission#

The binding energy of \(^{236}\textnormal{U}\) is \(7.587~\textnormal{MeV/nucleon}\). The average binding energy of nuclides with masses in the range \(A=87–103\) is about \(8.648~\textnormal{MeV/nucleon}\), and of those with masses \(A=130–145\) is \(8.384~\textnormal{MeV/nucleon}\).

Again allowing for two prompt neutrons, and taking typical fragment masses of \(95~u\) and \(139~u\), we deduce that the energy release is \(95 \times 8.648) + (139 \times 8.384) - (236 \times 7.587) = 196.4~\textnormal{MeV}\). This agrees well with the standard figure of \(\sim 200~\textnormal{MeV/fission}\).

The breakdown of this 200 MeV is, on average:

the two fission fragments have kinetic energies of about 98 and 66 MeV respectively;

the average neutron energy is about 2 MeV, so about 5 MeV is carried away by the neutrons;

about 8 MeV is emitted as prompt γ-rays;

the remaining 23 MeV comes from β and γ decays of fission fragments, about half of which is lost as neutrino kinetic energy.

Thus, most of the energy release comes in the form of the kinetic energy of the fission fragments. This will quickly be redistributed among neighbouring atoms as the recoiling fragments collide with them, so the overall effect is to heat up the uranium.

11.2.2. Chain reactions#

If at least one of the neutrons released by a \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) fission manages to induce fission in another \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) nucleus, we have a chain reaction. There are three possible scenarios:

If the number of neutrons inducing a further fission is <1, the system is sub-critical and the fission process will not sustain itself.

If the number is >1, the fission rate will increase exponentially. This is a super-critical system (otherwise known as a bomb…)

For controlled energy release, i.e. power generation, we want the number to be exactly 1 (critical) for steady-state operation, but controllable (since we will need >1 for starting up and <1 for shutting down).

This is where delayed neutrons are essential. If all neutrons were prompt, the timescale for the exponential runaway of supercriticality would be so fast that effective control would be impossible. The existence of the delayed neutron component means that a chain reaction that is exactly critical is actually slightly subcritical in prompt neutrons, which means that the timescale for supercriticality is set by the half-lives of the neutron-emitting fission fragments. These vary considerably, from a fraction of a second to around a minute, but the average is around 1.7 s, which is long enough to allow effective control.

(It is worth noting here that the delayed neutron yield of \(^{239}\textnormal{Pu}\), which is produced in reactors by neutron capture on \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\) followed by β decays of \(^{239}\textnormal{U}\) and \(^{239}\textnormal{Np}\), is much lower, at 0.0065 neutrons per fission. This makes controlling a reactor that uses plutonium fuel more difficult than a reactor whose fuel is mostly \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\).)

11.2.2.1. Startup sources#

The need to keep the prompt neutron yield subcritical makes starting up a nuclear reactor slightly tricky. It is normally done by inserting a startup source in the reactor core to initiate the chain reaction. Any of the radioactive neutron sources discussed in the previous units will do: the usual choice is \(^{252}\textnormal{Cf}\), because its neutrons have a very similar energy spectrum to those from uranium fission, so the reactor is designed for them, but an AmBe or PuBe source can be used instead. The startup sources are usually deployed temporarily at the start of reactor operation, replacing a few of the fuel rods, and are withdrawn once the chain reaction is established.

11.2.2.2. Subcritical reactors#

Startup sources supply additional neutrons to an initially subcritical chain reaction. Some reactor designs have been proposed that would always be subcritical, with the additional neutrons needed to maintain the chain reaction supplied, for example, by a spallation source. The benefits of subcritical reactors are that they could use a wider range of fuel, especially long-lived nuclear waste (such as neptunium, americium and curium, which have isotopes with half-lives of thousands to millions of years) and thorium (which is more abundant on Earth than uranium), and that they allay many concerns about reactor safety, since they are inherently incapable of going supercritical (but, as we saw with Fukushima, a successfully shut-down reactor can still pose a safety hazard, because fission product decays will continue to heat the reactor core after the chain reaction has stopped). The disadvantages are high cost and concerns about reliability (if the accelerator for the spallation source goes offline, the reactor will shut down). Although subcritical reactors have some vociferous supporters, they have so far failed to win over the nuclear industry.

11.2.3. Reactor design#

11.2.3.1. The four-factor formula#

The design goal of a nuclear reactor is to maintain a precisely critical, and therefore stable, fission chain reaction. In order to do this, we must have exactly one neutron from each fission (including delayed neutrons) initiate another fission reaction. There are four factors that determine this number:

η is the number of neutrons per fission that are available to be thermalized (i.e. are not absorbed in (n,γ) reactions on uranium);

ϵ is the enhancement factor accounting for fission of \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\) by fast neutrons;

p is the probability that the neutron avoids being captured by \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\) during thermalization, as it passes through the energy range where there are resonances in the cross section;

f is the fraction of thermal neutrons actually available for capture by \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) or \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\), i.e. not captured by the moderator or some other component of the reactor.

The combination of these is unsurprisingly known as the four-factor formula.

Natural uranium does not spontaneously initiate chain reactions (fortunately), so we can conclude that under natural conditions \(k<1\). The aim of reactor designers is therefore to enhance \(𝑘\) to achieve criticality, while maintaining control.

11.2.3.2. Reactor design strategies#

The cross section for neutron-induced fission on \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) is much higher for thermal neutrons than it is for the fast (~2 MeV) neutrons emitted during fission, so the first strategy for increasing 𝑘 is to moderate the neutrons. This strategy is adopted by nearly all reactor designs.

The number of neutrons initiating a new fission reaction, 𝑘, can then be increased in a variety of ways.

Increase η (and p) by isotopically enriching the uranium fuel so that it contains more \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\), thus increasing the probability that the neutron encounters a \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) nucleus rather than \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\). Most commercial reactor designs do this, enriching the fuel to 3.5–5% \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\).

Increase \(p\) and \(f\) by optimising the moderator. If the neutrons thermalize quickly, this reduces the time they spend in the energy range corresponding to the \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\) resonance region (roughly 5 eV to 5 keV). If the moderator has a low neutron capture cross section, the fraction of neutrons being captured by the moderator is decreased, leading to an increase in the fraction available for capture by \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\).

We saw above that the optimal moderator is deuterium, \(^{2}\textnormal{H}\): this is nearly as efficient as ordinary hydrogen in thermalizing neutrons, but has a much lower neutron capture cross section. Therefore, this strategy can be implemented by using deuterium, normally in the form of heavy water, \(\textnormal{D}_{2}\textnormal{O}\), as the moderator. This is done in the pressurised heavy water reactor design.

Alternatively, we can choose not to moderate, and rely on inducing fission with fast neutrons. This requires a higher level of initial enrichment, because the ratio between the fission cross section and the neutron capture cross section is much lower for fast neutrons than for thermal neutrons. However, fast neutron captures on \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\) produce the fissile isotope \(^{239}\textnormal{Pu}\), so a fast reactor can be designed to produce more fissile fuel than it consumes (such a reactor is known as a fast breeder reactor).

Fast reactors are very efficient in terms of fuel usage, and produce less waste than the usual moderated designs. However, they have proved expensive to build and operate. One problem is that water cannot be used for cooling, because it is a moderator; the solution adopted is to let the reactor run very hot, around 500 °C, and cool with liquid metal. This obviously means that the construction materials have to be able to withstand such temperatures, and as the metal most commonly used is sodium, coolant leaks can be hazardous. It also makes startup much more complicated, as the reactor has to be heated up to a point where the metal coolant is liquid before the reactor can operate.

Fast reactor designs, especially fast breeders, were intensively studied in the 1950s and 60s, when the supply of uranium was thought to be very limited. However, commercial uranium supply increased significantly through the 1970s, and at the same time increased concerns over safety and radioactive waste caused a slowdown in the rate of reactor construction. The combination of these effects meant that the perceived need for fast reactors was greatly reduced, and their economic competitiveness effectively disappeared.

11.2.4. Common reactor designs#

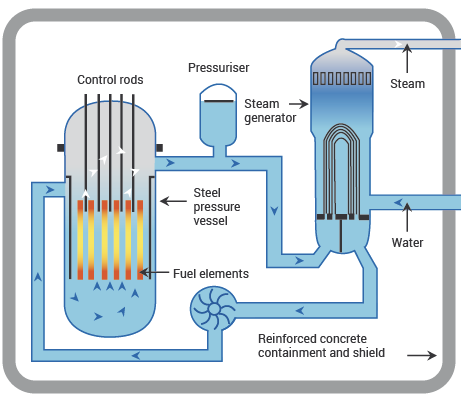

A typical reactor design includes the following components:

fuel, generally pellets of uranium oxide (\(\textnormal{UO}_{2}\)) packed into tubes to form fuel rods;

moderator to thermalize the neutrons—depending on the design, this may be water, heavy water or graphite;

control rods made of a neutron absorber (typically cadmium, hafnium or boron) to reduce power output or shut down the reactor as required;

coolant to transfer the heat from the reactor core;

pressure vessel or pressure tubes containing the reactor core, moderator and coolant;

steam generator using the heat transferred by the coolant to produce steam, which powers the steam turbines that generate electricity;

containment vessel to isolate the reactor from its surroundings (protecting the reactor during normal operation, and the surroundings in case of malfunction).

Not all designs have every one of these components—for example, a fast reactor does not have moderator, and a boiling water reactor does not have a steam generator—but they all have most of them.

11.2.4.1. Pressurised water reactor (PWR)#

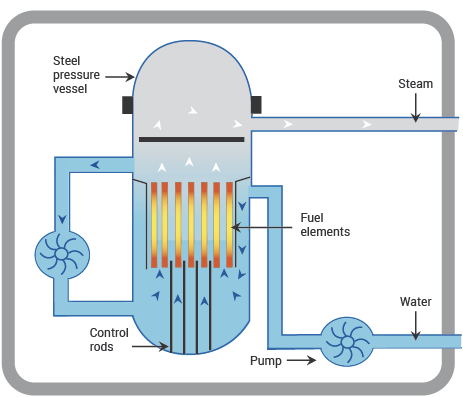

Fig. 11.4 schematic diagram of a PWR, showing main components. From https://world-nuclear.org.#

PWRs use ordinary water as both moderator and coolant. Because the reactor core operates at temperatures of around 325 °C, well above the boiling point of water, the water must be maintained at very high pressure (around 150 bar) to keep it liquid (and therefore dense enough to be an effective moderator). Therefore, there is a secondary cooling circuit, under less pressure, which generates steam to power the turbines that generate electricity.

If the reactor overheats, the water in the primary cooling system will boil, reducing its efficiency as a moderator and therefore reducing the fission rate. This negative feedback is a useful safety feature. PWRs require enriched fuel. A typical large power-station reactor contains 80–100 tons of uranium.

PWRs are the most common type of power-station reactor worldwide, and are also the type used to power nuclear submarines. Their main disadvantage is that it is hard to vary power output to meet variable demand, a feature known as load-following. PWRs are most economical when run at full capacity all the time, so they work best in a mixed economy with a range of different types of power plant (they can then handle the base load that doesn’t change, while other technologies get switched on and off to meet demand).

11.2.4.2. Boiling water reactor (BWR)#

Fig. 11.5 schematic diagram of a BWR, showing main components. From https://world-nuclear.org.#

BWRs are the second most common type of reactor worldwide. As the name indicates, the main difference between BWRs and PWRs is that in BWRs the primary cooling water is allowed to boil. (It is still at very high pressure, just not as high as in a PWR—about 75 bar as opposed to 150.) The top of the core is surrounded by steam, rather than liquid water, and is thus less efficient, as the neutrons are less effectively moderated.

In the BWR the steam from the top of the core goes directly to the turbines, and there is no secondary cooling circuit. This makes the design simpler, as you can see by comparing figures 10.4 and 10.5, but the disadvantage is that the water that goes to the turbines is slightly radioactive from neutron activation, so the turbine hall is part of the reactor complex and has to be shielded and operated under appropriate radiation-protection protocols. Fortunately, the radioactivity of the water is very short-lived, so access to the turbine hall is possible when the reactor is shut down, e.g. for refuelling.

BWRs are better at load-following than PWRs, which makes them a good design for countries that rely heavily on nuclear power. Like PWRs, they require enriched fuel. They tend to be slightly larger than PWRs, with up to 140 tons of uranium.

11.2.4.3. Pressurised heavy-water reactor (PHWR)#

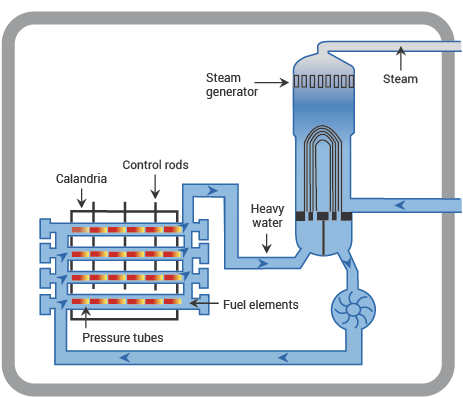

Fig. 11.6 schematic diagram of a PHWR, showing main components. From https://world-nuclear.org.#

In principle, the design of a PWHR is exactly the same as a PWR, except for using heavy water instead of ordinary water in the primary cooling circuit. The CANDU design in Figure 11.6 looks different from Figure 11.4 because it uses pressure tubes instead of a monolithic pressure vessel. The advantage of this design is that the reactor can be refuelled on-load, without shutting down, by isolating one pressure tube from the cooling circuit.

CANDU reactors use natural uranium, and can accept a variety of other fuels, including spent fuel from light-water reactors. They run slightly less hot than a standard PWR, with the heavy water at a pressure of around 100 bar and a temperature of 290 °C.

The features of the CANDU design are not so much deliberate choices as a consequence of the desire to build the reactors entirely in Canada. In the 1960s Canada had no uranium enrichment capability, hence the choice of a design that could use natural uranium, and there were doubts that Canadian industry could build the large monolithic pressure vessel shown in Figure 11.4, hence the choice of pressure tubes. Nevertheless the CANDU is a successful and flexible design that has been exported to several other countries, notably India.

11.2.4.4. Advanced gas-cooled reactor (AGR)#

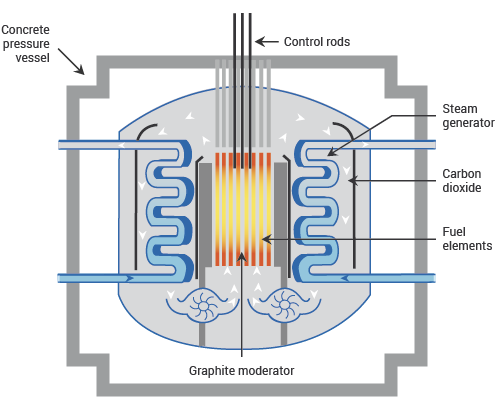

Fig. 11.7 schematic diagram of a AGR, showing main components. From https://world-nuclear.org.#

The AGR is an uncommon design worldwide, but it is a British design and is the dominant type in the UK, so worth including here. As the name suggests, the distinguishing feature of the AGR is that the coolant is a gas, namely \(\textnormal{CO}_{2}\), rather than a liquid. Gas is fairly useless as a moderator owing to its low density, so in this design the coolant and the moderator are separate. AGRs use graphite as a moderator: it is less efficient, but as a solid it is easier to use.

Having a gaseous coolant means that AGRs run hotter than PWRs, at about 650 °C. This produces higher-temperature steam, which increases the thermal efficiency of the turbines. The name advanced gas-cooled reactor comes from the fact that the design evolved from the older British Magnox reactors, which used the same basic ingredients of \(\textnormal{CO}_{2}\) cooling and graphite moderator, but ran on natural uranium metal instead of enriched uranium oxide. (AGRs require slightly enriched uranium because their higher operating temperature meant that the magnesium-clad fuel rods used in the Magnox design would not work, and the high-temperature design turns out to absorb more neutrons, decreasing f in the four-factor formula.) The original 1950s Magnox design was specifically intended as a dual-purpose facility, both generating electricity and breeding plutonium for Britain’s nuclear weapons programme; the AGR design, however, was always intended purely for electricity generation.

11.2.5. Reactor power output#

Since nuclear reactors do not generate electricity directly, but instead generate heat which is then used to generate energy via a steam turbine, there are different ways of specifying the power output of a reactor.

The thermal power output, measured in MWt, is the amount of heat generated, and is determined from the properties (pressure, temperature, rate of flow) of the steam produced by the reactor.

The gross electrical power, measured in MWe, is the electrical power produced by the turbines.

The net electrical power, also measured in MWe, is the electrical power supplied to the grid. This is less than the gross electrical power, because some of the electricity that is generated is used to power the plant itself (e.g. the coolant and steam generator pumps for the reactor).

From the perspective of the consumer (or the electricity company), the appropriate power output is the net electrical power. For the perspective of the reactor engineer (or neutrino physicist) the relevant power output is the thermal power.

11.2.6. A natural nuclear reactor (not examinable)#

We have said that natural uranium cannot sustain a chain reaction, and most nuclear reactor designs require enriched uranium. However, the half-life of \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) is much less than the half-life of 238U, so if we go back in time the concentration of \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) in natural uranium must get higher. Natural uranium two or three billion years ago would have a composition similar to reactor-grade enriched uranium today. So, could this have sustained a natural chain reaction?

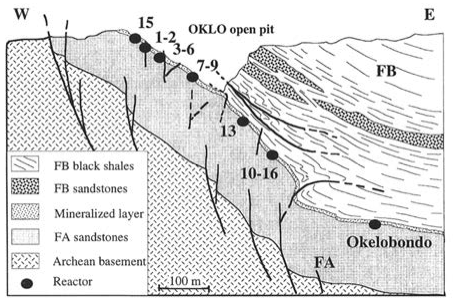

Fig. 11.8 geology of the Oklo uranium mine, showing the locations of the natural nuclear reactors. ‘FA’, ‘FB’ are specific geological units.From Gauthier-Lafaye, Holliger and Blanc, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60 (1996) 4831.#

The answer to this turns out to be “yes”. In 1972, a French uranium enrichment plant found that uranium samples from the Oklo mine in Gabon, Africa, contained significantly less \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) than the usual 0.72%. This was of course immediately investigated, since “missing” fissile material is a very alarming occurrence, and it was found that the reason for the discrepancy was that at least 16 separate natural nuclear reactors had operated in this uranium seam around two billion years ago. Because the region is geologically very stable, the resulting depletion of fissile \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) (and enhancement of the abundance of fission product nuclei) remained concentrated in the regions in which these self-sustaining chain reactions had happened.

It appears that the reason for this phenomenon is that groundwater penetrated this seam of high-grade uranium ore, acting as a moderator and therefore allowing a chain reaction to occur. The conditions in the ore were similar to those inside a modern boiling-water reactor. It seems that each reactor operated in pulses about 30 minutes long, with the chain reaction dying off when it had generated enough heat to boil off the groundwater and then restarting when the heat died down and liquid water returned, the full cycle taking about three hours. Each reactor probably generated in the region of 20 kWt when operating, and it is estimated that overall about 130 TWh (\(4.7 \times 10^{17}~\textnormal{J}\)) of heat was produced.

The Oklo natural nuclear reactors are, so far, essentially unique (there is a 17\(^{\textnormal{th}}\) reactor at Bangombé, about 30 km away from Oklo). This is because the conditions for initiating a natural self-sustaining chain reaction are quite demanding:

The uranium ore must be high-grade, with a high concentration of uranium (the Oklo ore is up to 15% uranium).

The deposit must be old enough that it dates back to the time when natural uranium was sufficiently rich in 235U (most high-grade uranium ore deposits are younger than Oklo).

There must be a suitable moderator present (water in this case).

The surrounding geology must not be too rich in “neutron poisons” (elements with high neutron capture cross sections, such as boron or cadmium).

Although the vast majority of uranium deposits will not meet all these conditions, it is quite likely that other natural nuclear reactors have operated, but have not left detectable traces because geological processes have disrupted the local area (there are not too many regions in the world where undisturbed two-billion-year-old sedimentary formations can be found), or simply have not been discovered yet.

Apart from their intrinsic interest, the Oklo natural reactors are an interesting testbed for the behaviour of nuclear waste: studies have been conducted to see how far the detectable fission products, especially the long-lived isotopes such as the actinides (the elements with atomic numbers 89 to 103), have travelled from their site of production. (The encouraging answer seems to be, not very far at all.)

11.2.7. Summary (fission)#

In principle, any nucleus heavier than iron has a positive \(Q\)-value for decay, and elements significantly heavier than iron should be capable of fission. However, the Coulomb barrier produced by the limited range of the strong force compared to the electromagnetic force means that many nuclei heavier than iron are perfectly stable: this fission barrier is too high to surmount and too think to tunnel through. No naturally occurring isotope has any significant branching ratio to spontaneous fission.

Using the liquid-drop model, we can calculate that spontaneous fission should happen if \(Z^{2}/A \geq 49\). This is an overly pessimistic estimate, because it is based on classical physics and does not take quantum tunnelling into account, and it is also subject to modifications based on the shell model (nuclei with closed shells of either protons or neutrons being more resistant to fission). However, it is still true that only very heavy nuclei are likely to have a significant decay branching ratio to spontaneous fission. It is noticeable that even-even nuclei are much more fission prone than even-odd nuclei.

To harness fission for energy generation, we rely on induced fission: neutron capture on an even-odd heavy nucleus may create an excited state of an even-even nucleus with energy above the fission barrier. An isotope which does this is referred to as being fissile. The most important fissile isotopes are \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) and \(^{239}\textnormal{Pu}\): \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) is naturally occurring and makes up 0.72% of natural uranium, while \(^{239}\textnormal{Pu}\) is produced by beta decays when a neutron is captured by \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\).

When a heavy nucleus fissions, it does so asymmetrically, with the heavy fragment consistently having an atomic mass around 139, while the lighter fragment gets whatever’s left (so, the heavier the fissioning nucleus, the heavier the light fragment). This effect is caused by the neutron magic number 82, which occurs in stable isotopes with masses from 136 to 144. The fission fragments are extremely neutron-rich, and will undergo several beta decays before reaching stability.

A few neutrons (2.4 on average, for \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\)) are emitted during the fission process, i.e. within the \(10^{−16}~\textnormal{s}\) timescale of a compound-nucleus reaction. These are prompt neutrons, and have an average energy of about \(2~\textnormal{MeV}\). In addition, some fission fragments may decay by neutron emission, producing delayed neutrons on a timescale of around half a second. There are about \(0.0162\) delayed neutrons per fission of \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\), on average.

The fact that neutrons are emitted during fission opens up the possibility that the first fission may cause further fission reactions. This is known as a chain reaction. The key property of a chain reaction is how many neutrons from any one fission reaction go on to induce further fissions. If this number is less than one, the reaction is subcritical, and will die out unless further neutrons are supplied from outside. If the number is greater than one, the reaction is supercritical, and its rate will increase exponentially—this is the situation in a nuclear explosion. To maintain a stable, controlled chain reaction, we need the number of neutrons per fission that induce a further fission to be (on average) exactly one: this is a critical chain reaction and will maintain a steady state indefinitely.

Exact criticality is an unstable equilibrium: if the number of neutrons per fission inducing a secondary fission event deviates either side of one, the effect is to push the number still further from one. Therefore it is essential to monitor and control the reaction rate to maintain precise criticality. This is only possible because of the delayed neutrons: if all neutrons were prompt, the timescale for a supercritical runaway would be so short that reactors would be hopelessly unstable. The extra half-second or so provided by the delayed neutrons is just enough to provide control and allow stable operation.

The number of neutrons per fission that induce another fission is determined by the four-factor formula , where \(η\) is the number of neutrons per fission available to be thermalized (i.e. not promptly captured by a uranium nucleus), \(ϵ\) is an enhancement factor accounting for the fact that fast neutrons can induce fission in \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\), \(p\) is the probability that the neutrons avoid being captured as they pass through the resonance region in the cross section of neutron capture on \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\), and \(f\) is the fraction of thermal neutrons that are captured by \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) rather than anything else in the reactor. In natural uranium, and self-sustaining chain reactions do not occur (though this was not the case a few billion years ago).

Commercial reactor designs employ one of two strategies: increase \(η\) (and to a certain extent \(p\) and \(f\)) by enriching the uranium so that a higher proportion of uranium nuclei are \(^{235}\textnormal{U}\) (PWR, BWR and AGR designs), or increase \(p\) and \(f\) by optimising the moderator (CANDU). Both strategies work; both have advantages and disadvantages. A somewhat different approach is to dispense with moderation altogether and induce fission with fast neutrons (a fast neutron reactor). Fast neutron reactors have the potential to be much more efficient in their use of uranium (because they “breed” fissile \(^{239}\textnormal{Pu}\) by neutron capture on \(^{238}\textnormal{U}\)), but are expensive to build and run, and not currently commercially competitive.

Nuclear reactor power output is quantified in three ways: the thermal power output, measured in MWt, which is the heat produced by the reactor, the gross electrical power, which is the electrical power output from the turbines, and the net electrical power, which is the electrical power supplied to the grid. Electrical power is measured in MWe.

11.3. Fusion#

11.3.1. Energetics of fusion#

Fusion is the combination of two nuclei into one. As can be seen from figure 11.1, it should release energy if the fusing nuclei are lighter than iron.

Nuclear fusion is the power source of stars, nearly all of which generate energy by fusing hydrogen into helium^2. Fusion energy is an attractive prospect for us too, because it is clean—no CO2 and no long-lived radioactive waste—and highly efficient. While uranium fission releases 200 MeV per fission of one nucleus of \(^{236}U\), corresponding to the conversion of 0.09% of the initial mass into energy, hydrogen fusion, \(4p \rightarrow ^{4}He + 2e^+ + 2\nu_e\), releases 24.7 MeV, plus another 2.0 MeV when the two positrons annihilate with electrons—a net efficiency of 0.7%, or eight times better than uranium fission. However, fusion is far more challenging to achieve than fission, because it requires two positively charged nuclei to approach very close to one another, against their mutual Coulomb repulsion.

11.3.2. The Coulomb barrier#

The potential energy of two charges \(Z_1e\) and \(Z_2e\) separated by a distance r is \(Z_1Z_2e^2/(4\pi\epsilon_0r)\). Therefore, the potential energy of two nuclei just touching one another is

where the nuclear radii \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) are measured in fm. Classically, in order to get the two nuclei to touch, we would need to supply enough initial kinetic energy to overcome this potential barrier, so for two protons of equal energy, the required kinetic energy would be 0.72/2.4 = 0.3 MeV. Equating this to \( \frac{3}{2}k_BT \) gives a temperature of \(2.3x10^9~\textnormal{K}\), which is about 200 times the actual temperature of the core of the Sun. The reason that the Sun can fuse hydrogen despite this apparent mismatch is quantum tunnelling: the Schrödinger equation tells us that there is a small but nonzero probability that the protons will “tunnel” through the potential barrier, even though they do not appear to have enough energy to do so. This probability is very small in the Sun, about \(10^{-9.6}\), but the Sun contains a very large number of protons!

11.3.3. Fusion reactions#

Another issue with proton-proton fusion is that there is no bound state of two protons: in order for the fusion to work, one proton has to transform into a neutron, \( p + p \rightarrow d + e^+ + \nu_e \). This is a weak interaction, and therefore has a very small cross section, further increasing the improbability of pp fusion—again, it works in the Sun because of the immense number of protons present in the Sun’s core. Although we can increase the tunnelling probability by running a hypothetical fusion reactor at a higher temperature than the solar core, we cannot magically increase the cross section for pp fusion, so the inescapable conclusion is that this is not an appropriate reaction for fusion power.

For viable fusion with the fuel masses we can hope to use in a terrestrial fusion reactor, we need reactions that can go by the strong interaction, requiring only rearrangement of nucleons rather than transformation of protons to neutrons or vice versa. We also need to restrict ourselves to the lightest elements, or more precisely to those with the lowest Z, because higher Z increases the height of the Coulomb barrier and therefore reduces the tunnelling probability. We are left with two main possibili- ties:

d-d fusion, \( ^2H(d,n)^3\textnormal{He} \) or \( ^2H(d,p)^3H \) (these two reactions are almost equally likely and have very similar Q values, 3.3 and 4.0 MeV respectively);

d-t fusion, \( ^3H(d,n)^4\textnormal{He} \), with a Q value of 17.6 MeV.

Note

In the later stages of a star’s life, it will generate energy by fusing helium to carbon, and in the case of stars with mass greater than about 8-10 times that of the Sun, heavier elements right up to iron. But the vast majority of stars are low-mass K and M dwarfs, and none of these has yet left the main sequence—so nearly all stars are powered by hydrogen fusion.

As we will see later, the second of these is much the more promising: not only does it have a much higher \(Q\) value, it also requires lower temperatures and has a higher reaction rate. Its main drawback is that it requires tritium, which is radioactive with a half-life of 12.3 years (it β decays to \( ^3\textnormal{He} \)), and which therefore does not occur in nature and has to be manufactured. Deuterium, in contrast, comprises about 0.015% of natural hydrogen and can be extracted from seawater.

It is worth noting that two deuterium nuclei cannot fuse to produce \( ^4\textnormal{He} \), as one might expect: the Q value of 23.8 MeV is well above the nucleon separation energy for \( ^4\textnormal{He} \), so a proton or neutron is emitted immediately and either tritium or \( ^3\textnormal{He} \) is produced instead.

The other two reactions that are sometimes considered for terrestrial fusion are

\( ^3\textnormal{He}(d,p)^4\textnormal{He} \), with a Q value of 18.3 MeV;

\( ^{11}\textnormal{B}(p,2α)^4\textnormal{He} \), with Q = 8.7 MeV.

These are favoured because they are both aneutronic fusion, with all the products being charged particles. In principle, aneutronic fusion has many advantages over d-d and d-t fusion: the products can be steered using magnetic fields, so there will be no ionising radiation or radioactive isotopes such as are produced by neutron capture, and the fast-moving charged particles can be used to generate energy directly, by induction, instead of indirectly by heating steam to power turbines, with significantly improved efficiency as a result.

Unfortunately for the proponents of aneutronic fusion, both of these reactions involve nuclei with higher Z and therefore higher Coulomb barriers than d-d or d-t fusion. Given that ignition tempera- tures even for d-d and d-t fusion are at the limit of current technology, it is clear than aneutronic fusion is currently not a viable proposition.

11.3.4. Fusion reaction rates#

The general formula for the rate of events in any reaction is \( R = n_1 \sigma \Phi \). Where \( \Phi \) is the incoming flux, \( n_1 \) is the number density of target particle and \(\sigma\) is the cross section. This assumes that the target particles are stationary. If the incoming particles are travelling with speed \( v \) and have number density \( n_2 \), then the flux is \( Φ = n_2v \), so overall we have \( R_{12} = n_1n_2σv \).

This would (and does) apply to the case where the incoming particles are in the form of a monoenergetic beam. However, in the case of fusion energy, we are raising the particle kinetic energy by heating them to a very high temperature, so the energies and speeds are given by the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. We therefore have to average over speed, and, since the cross section is a strong function of energy, also over cross section. We can therefore write the reaction rate as

The quantity \( ⟨σv⟩ \) is known as the reactivity. In the case of d-d fusion, particles 1 and 2 are indistin- guishable, so to avoid double counting we have to write \( R_{dd} = \frac{1}{2}n^2⟨σd_dv⟩. \)

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution gives

where \( v \) is the relative speed of the two nuclei and \( m = (m_1 m_2)/(m_1 + m_2) \) is the reduced mass.

The cross section is given by

where \( E_G = 2m e^2 (\pi \alpha Z_1 Z_2)^2 \) is the Gamow energy and describes the probability of tunnelling through the Coulomb barrier (as in a decay). The factor \( S(E) \) depends on the particular nuclei involved, but its energy dependence is typically quite weak so we can treat it as a constant.

We can convert \( P(v)dv \) from a function of speed to a function of energy by noting that for non-relativistic velocities \( E = \frac{1}{2} mv^2 \), so \( dE = mvdv \). Then

Hence our average

Although the integral is over the whole energy range between 0 and ∞, \( e^{-E/k_B T} \rightarrow 0\) at large \(E\) (we run out of particles) and \( e^{-E_G/E} \rightarrow 0\) at small \(E\) (the barrier becomes too thick to tunnel through). Neglecting the slow variation of \( S(E) \) and differentiating the exponential, we find that there is a maximum where

This means that for a given temperature, the particles that fuse actually come from a fairly restricted energy range in the tail of the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

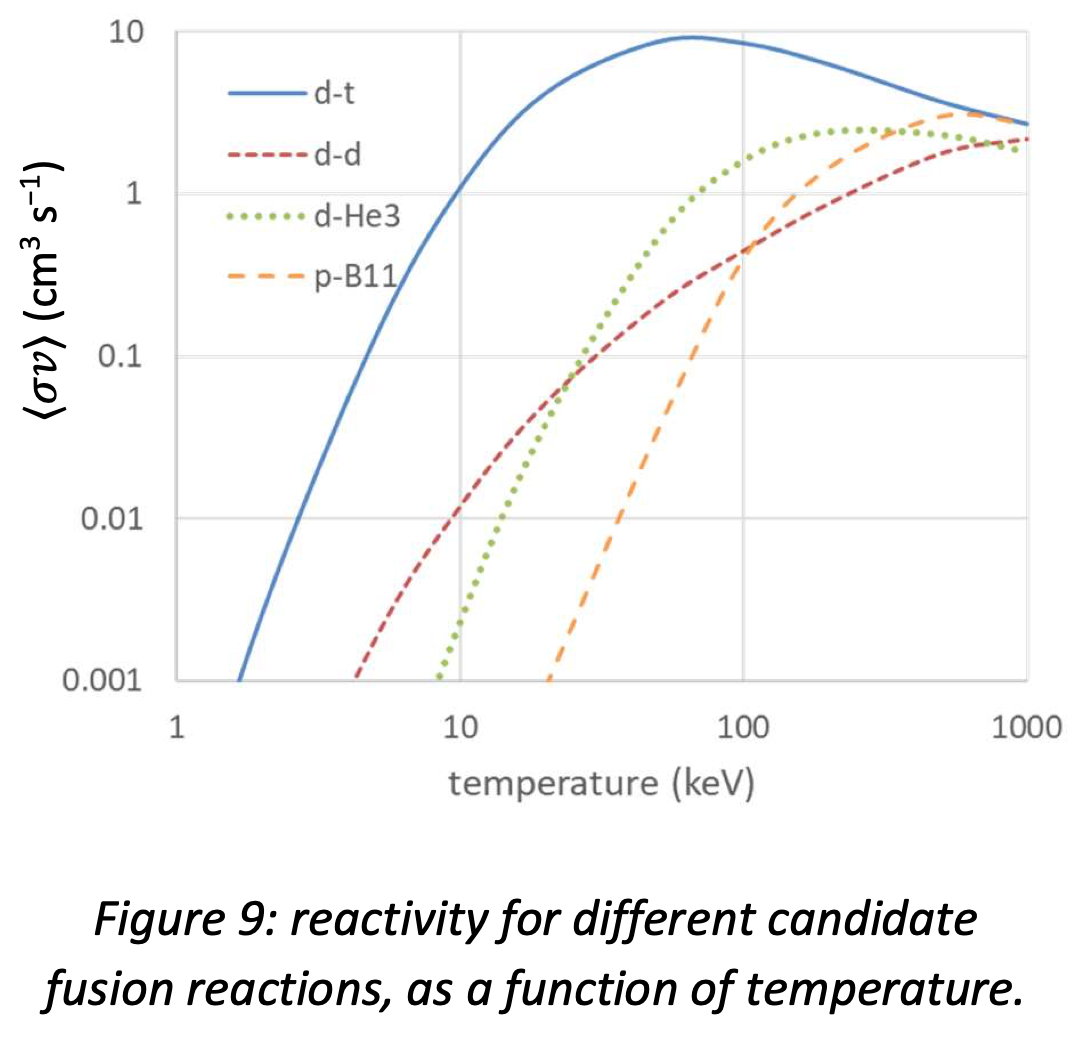

Calculating \( \langle \sigma v \rangle \) for the candidate fusion reactions listed in the previous section gives the results shown in figure 11.9. There is a clear winner: d-t fusion has the highest peak reactivity and turns on at the lowest temperature. The effect of the higher Coulomb barrier for the two aneutronic reactions is clearly seen: \(\textnormal{p-}^{11}\textnormal{B}\) fusion in particular requires temperatures about ten times higher than d-t fusion.

The temperatures in figure 11.9 are shown in keV. The conversion uses \( E = k_B T \), so \(1\) keV = \(11.6\times 10^6\) K (the temperature of the core of the Sun is therefore of order 1 keV). For a viable fusion reactor we will need to achieve temperatures of at least 10 keV; 20 or 30 keV would be better.

Fig. 11.9 Reactivity for different candidate fusion reactions, as a function of temperature.#

11.3.5. Deuterium-tritium fusion#

11.3.5.1. The challenges#

Anyone wishing to generate energy by d-t fusion has to overcome some obvious technical challenges:

From figure 9, it is clear the temperatures of at least 120 MK, and ideally twice that, must be achieved to obtain a high enough reactivity. Such temperatures would obviously vaporise any structural material, so the deuterium-tritium plasma must be kept away from the walls of its container.

Tritium is radioactive, so does not occur in nature, and the supply is very limited.

Since a kinetic energy of ~20 keV is negligible, we can assume that when the two nuclei fuse they are approximately at rest relative to each other, and so the momenta of the products must be equal and opposite. In this non-relativistic regime we can write the kinetic energy as \(p^2/2m\), so it follows that the kinetic energy of the products (a neutron and an \(α\) particle) is inversely proportional to their masses (about \(1 u\) and \(4 u\) respectively), which means that 80% of the energy produced is released as kinetic energy of the neutron. We must therefore extract this energy if the reactor is to be efficient.

11.3.6. The Lawson criterion and fusion strategies#

An economically viable fusion reactor must obviously generate more energy than it consumes. We can quantify this by defining the Lawson criterion,

(there are actually several definitions of the Lawson criterion, but this is the simplest). The minimum energy we need to input is the energy required to heat the plasma to the required temperature: assuming that the plasma consists of equal amounts of deuterium and tritium, equipartition of energy gives us \(E_{in} = 4 × \frac{3}{2} n_d k_B T~\) (for each deuterium nucleus, there is a tritium nucleus and two electrons, so four particles in all), and the output energy is the Q value times the number of reactions,

where \(t_c\) is the confinement time.

Putting in numerical values gives, for a temperature of \(20\) keV, \(n_d t_c = 7 × 10^{19}\)m\(^{-3}\) s. Therefore we need a very high plasma density, a very long confinement time, or (ideally) both.

Two strategies for achieving fusion power are currently being pursued:

magnetic confinement, in which the plasma is confined by a magnetic field and circulates around a toroidal reactor: this technique aims for long confinement times;

inertial confinement, in which a small pellet of fuel is heated (directly or indirectly) to extremely high temperatures by a battery of powerful lasers: this aims for very high density.

Both techniques are close to achieving breakeven, i.e. \(L = 1\), but both are far from commercialisation.

11.3.7. Magnetic confinement fusion (MCF)#

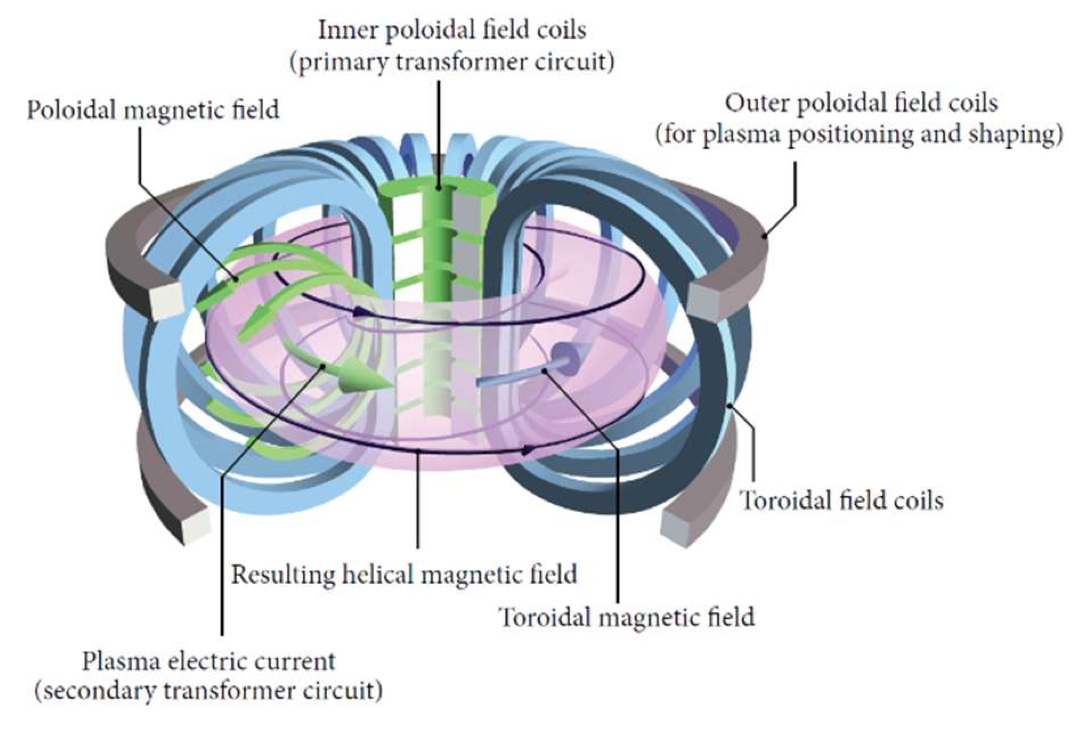

The principle of magnetic confinement fusion is that a complex magnetic field is used to keep the plasma away from the walls of the container. There are various magnetic geometries, but the most widely used and studied is the tokamak (a name derived from a Russian acronym, as this design was first developed in Russia). The aim of all magnetic confinement devices is to maintain the confinement of the plasma for an indefinitely long time, thereby increasing \(t_{c}\) to a very large value; the challenge is maintaining stability over long periods. Hot plasmas moving at high speeds are subject to a number of dynamic instabilities, and controlling these is the principal design challenge in tokamak research.

The principle of the tokamak design is that the magnetic field is helical (similar to the stripes on a traditional barber’s pole). This is required to main- tain stable confinement in a toroidal geometry; if the field simply went round the toroid, the geometry dictates that it would be stronger on the inside of the torus than the outside (if you think of bending a coil into a closed loop, there are clearly more turns per metre on the inside of the loop than the outside), and this caused the confined particles to drift sideways and eventually hit the wall. A helical field is more symmetrical and therefore the confined plasma is more stable. Achieving this requires a complex geometry of field coils, as shown in figure 11.10.

Fig. 11.10 magnetic field configuration in a tokamak. Figure from Li et al., Abtr. App. Anal. 2014 940965.#

Numerous tokamaks are currently operating around the world. One of the most successful is the Joint European Torus, JET, located at Culham, Oxfordshire. Two next-generation designs, the International Thermonuclear Reactor (ITER), under construction in Cardarche, France, and the MIT-led SPARC in Massachusetts, aim to achieve 𝐿 ∼ 10 within the next decade or so. A South Korean project, K-DEMO, aims to achieve stable energy generation of around 500 MWe some time in the 2040s.

11.3.8. Inertial confinement fusion (ICF)#

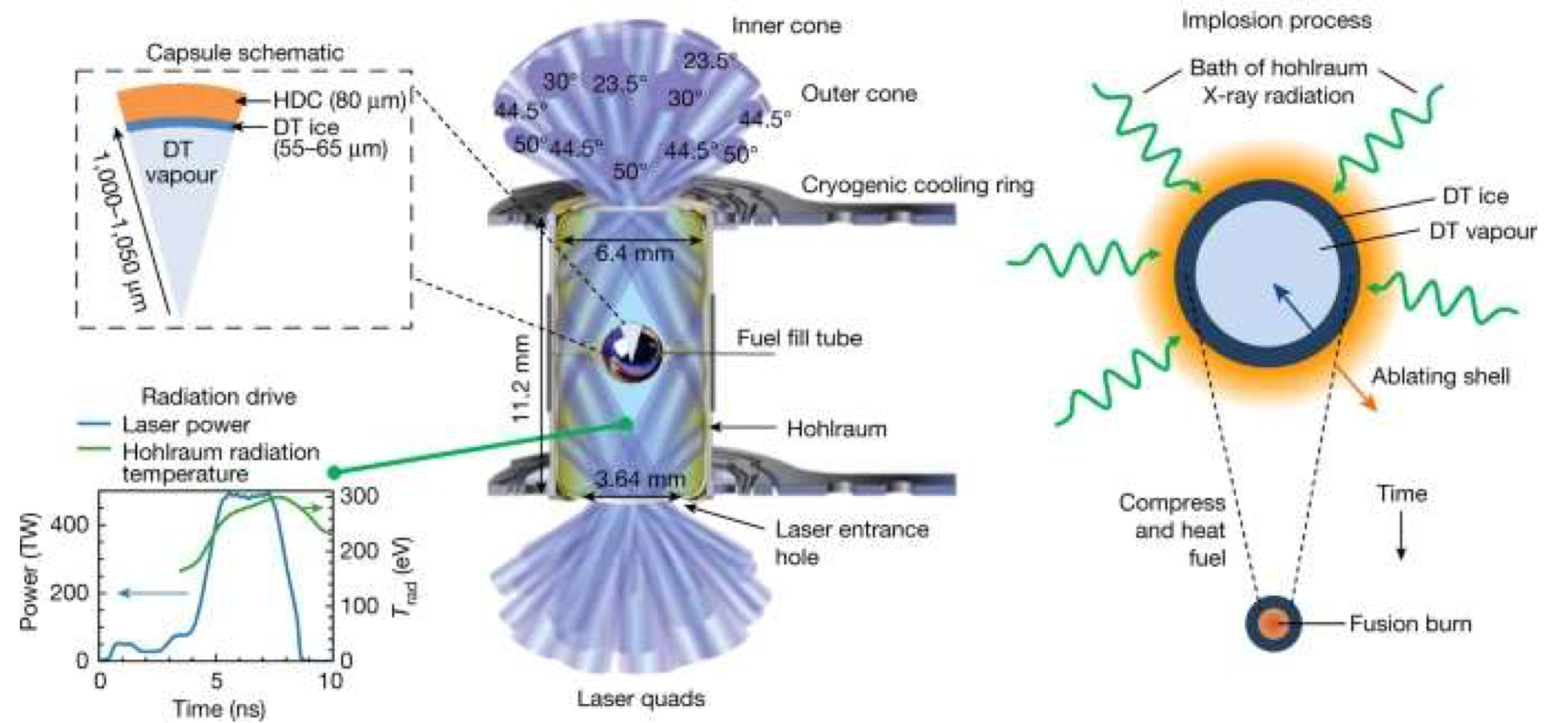

Inertial confinement systems achieve fusion by compressing and heating a small pellet of fuel. The outer layers of the pellet explode outwards on heating, generating a shockwave which propagates inwards and initiates fusion in the core of the target.

The heat is provided by a battery of powerful lasers. There are two basic strategies, direct drive, in which the lasers heat the fuel pellet directly, and indirect drive, in which the fuel pellet is contained inside a small metal cylinder (known as a hohlraum), which the lasers heat up to a level at which it emits intense X-rays, which heat the fuel pellet. The direct-drive method is much more efficient, but requires very tightly focused laser beams, because the fuel pellet has to be very small to limit the effects of instabilities in the produced plasma. The combination of high power and small diameter in the laser beam array is a serious technical challenge. Conversely, indirect-drive systems are much easier to build, because the laser beam size is defined by the size of the hohlraum rather than the fuel pellet, but are much less efficient because the X-ray emission of the hohlraum is not focused on the target, so a great deal of the input laser energy is wasted.

The most advanced inertial confinement system is the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. NIF is an indirect-drive system using 192 laser beams (from 48 lasers) which deposit about 2 MJ of energy on the hohlraum. A schematic of the NIF target region is shown in figure 11.11. NIF achieved breakeven in one shot in December 2022, when 2.05 MJ of energy deposited on the hohlraum produced 3.15 MJ of fusion energy. (However, note that actually charging the lasers to produce that 2.05 MJ required a lot more than 2.05 MJ of energy input, so this is breakeven only in a technical sense.)

Fig. 11.11 NIF hohlraum and target, from Zylstra et al., Nature 601 (2022) 542.#

11.3.9. Steps towards practical fusion#

The key to achieving consistent energy generation in fusion reactors is self-heating. The α particle produced in the fusion reaction carries 20% of the fusion energy and has a very short range in matter, so it will deposit its energy in the plasma, helping it to maintain its temperature. A plasma that main- tains its temperature through α-particle heating, without needing further external input, is said to have achieved ignition. Self-heating was demonstrated in the NIF breakeven shot.

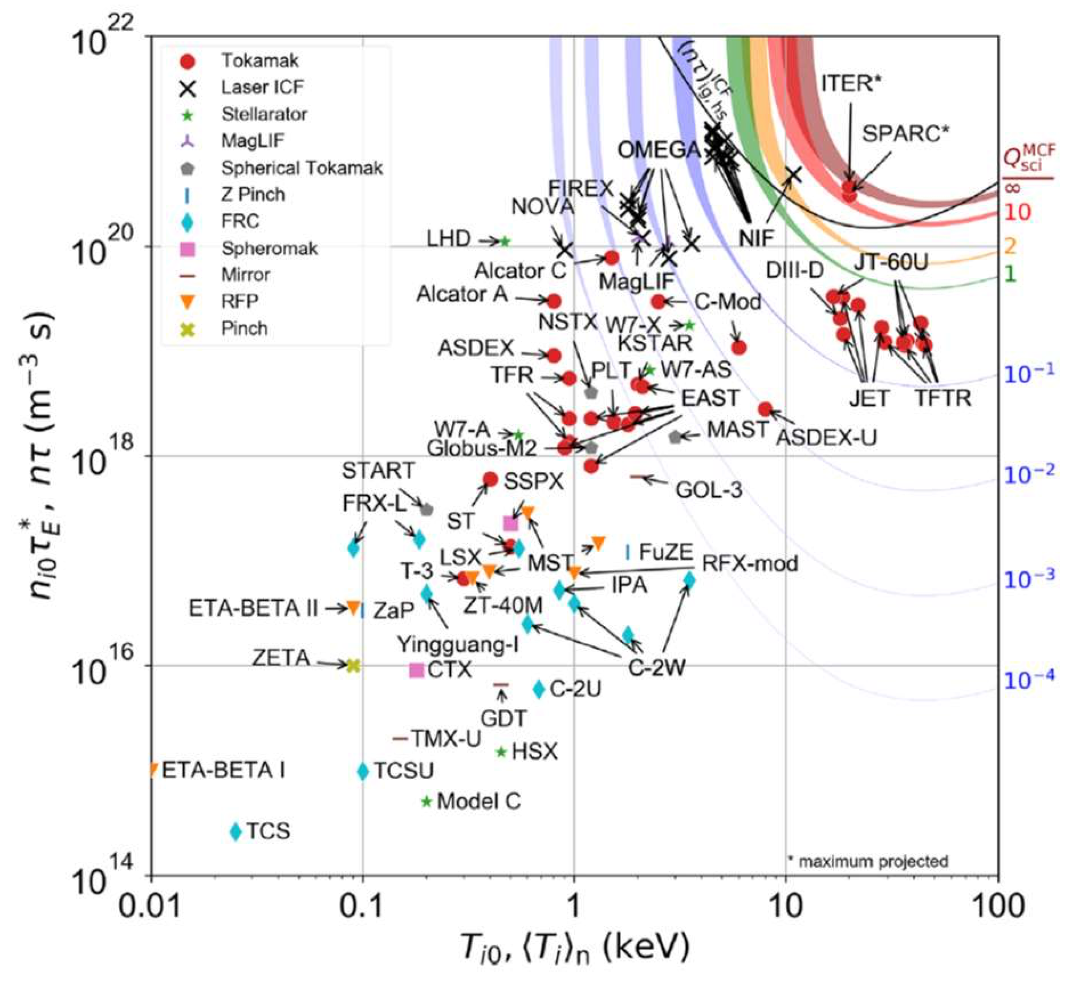

Practical fusion is proverbially “always 20 years in the future”, but figure 11.12 shows that in fact the perfor- mance of experimental fusion reactors has improved by orders of magnitude since work started in the 1950s. In this plot \(T_{i}\) is the ion temperature (averaged over the fuel pellet for ICF), \(τ\) is the pulse duration for ICF, and \(τE\) is the energy confinement time, i.e. the time it takes for energy equal to the plasma thermal energy (= the input energy) to leak away from the plasma (appropriate for long confinement times in MCF). The coloured curves represent the given values of what the authors call \(Q_{sci}\), which is the same as what we have called \(L\); the black curve is the hot-spot ignition threshold for ICF.

Fig. 11.12 Performance of experimental fusion reactors. The symbols represent the type of reactor: apart from “laser ICF”, most of these are different magnetic geometries for MCF. MagLIF is a hybrid approach using a combination of laser-driven compression and magnetic confinement. Figure from Wurzel and Hsu, Phys. Plas. 29 (2022) 062103.#

Key points that most of the experimental reactors have not considered, but which are essential to move from research to application, are how to extract the power and how to ensure a supply of tritium. Both of these are more easily addressed in MCF (I have no idea how one extracts the power from an ICF setup).

Assuming that the kinetic energy carried by the α particle is used for self-heating, the power to be ex- tracted is the kinetic energy of the neutron. As the neutron is not charged, it will not be confined and so will hit the reactor wall. The plan in the tokamak approach is to coat the internal wall with a blanket of some light element, which will absorb the neutron energy and produce heat. This heat would then be used to drive a steam generator as in fission reactors.

Furthermore, if the blanket were made of lithium, the neutron capture reactions \(^{6}\)Li(n,t)\(^{4}\)He and \(^{7}\)Li(n,nt)\(^{4}\)He could be used to “breed” tritium to power the reactor. This could in principle solve the tritium supply problem (though, as only one triton is produced per neutron capture, and only one neutron is produced per tritium fusion, the capture process would have to be very efficient).

ITER plans to test both heat extraction (with an actively cooled blanket designed to extract up to 736 MW of thermal power) and tritium breeding (although the blanket will initially be made of beryllium, installation of test modules containing lithium is planned at a later stage).

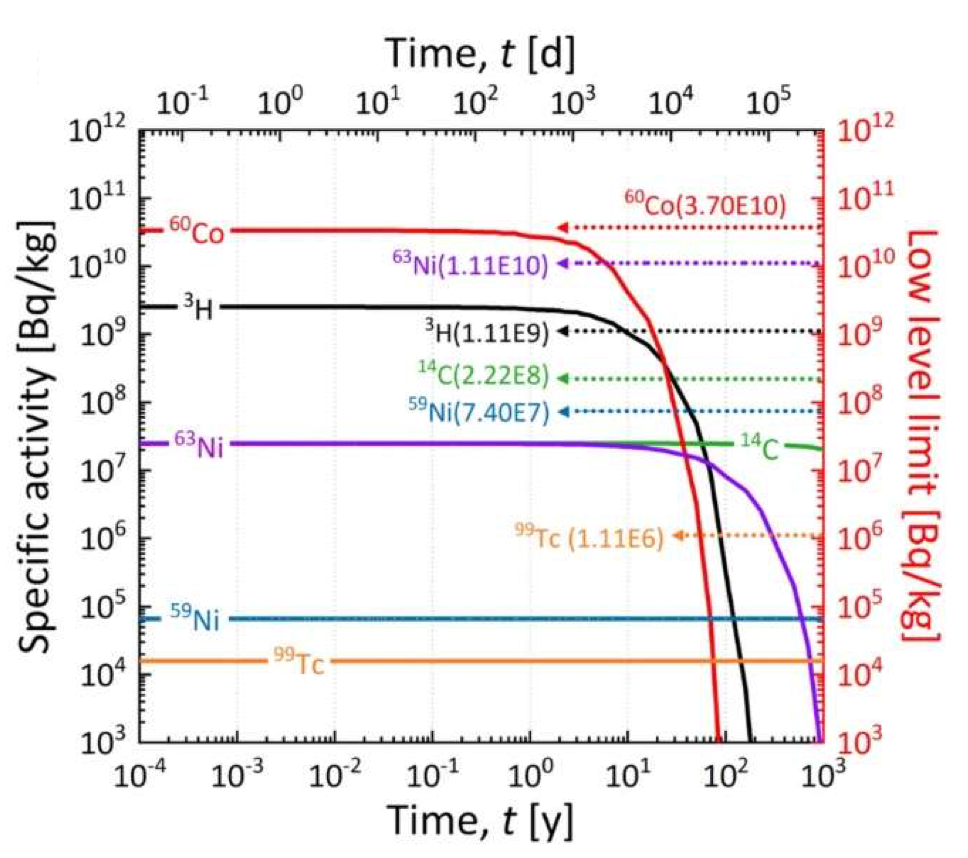

Practical fusion must also address the issue of radioactive waste, which has been a sticking point for fission reactors. Although in principle the fusion process does not generate radioactive products, some neutrons will inevitably be captured on materials other than the blanket, and in some cases this will lead to a radioactive isotope. This has been studied for the K-DEMO project, and the results are shown in figure 11.13. Although radioactive isotopes will be pro- duced, most have short half-lives, and fall below the Korean upper limit for “low-level waste” within at most 10 years after the reactor stops operating. This does not pre- sent a major technical challenge.

Fig. 11.13 Radioactivity of components of the K-DEMO fusion reactor, compared with legal limits for low-level waste. From Kim, Hong and Kim, Scientific Reports 12 (2022) 8276.#

11.3.10. Summary (fusion)#

Hydrogen fusion, the power source of stars, is in principle a highly efficient, clean energy source. However, fusion presents major technical challenges, primarily related to the extremely high temperatures needed to overcome the Coulomb repulsion of the two positively charged nuclei, and despite about 70 years of research a commercially viable fusion reactor has not yet been built.

The key physical parameter for fusion reactions is the reactivity ⟨𝜎𝑣⟩. Calculations of this parameter for various candidate fusion reactions show that by far the most promising is d-t fusion, \(^{3}\)H(d,n)\(^{4}\)He, which has both the lowest turn-on temperature and the highest peak reactivity.

The critical parameter for achieving breakeven in fusion (i.e. energy generated = energy input) is the product of the number density of the plasma and the time for which it is confined. The two strategies pursued to maximise this are magnetic confinement fusion, which aims to achieve long confinement times by trapping the hot plasma inside a carefully shaped magnetic field, and inertial confinement fusion, which aims to produce extremely high densities by compressing and heating a small fuel pellet using powerful lasers. Fusion ignition occurs when the fusion reaction rate gets to the point at which energy absorbed from the produced α particle (which has an initial energy of 3.5 MeV) is sufficient to maintain the plasma temperature without the need for further energy input.

The flagship projects at the present time are JET in the UK and the Japanese JT-60SA (essentially a prototype for ITER). JT-60, the predecessor of JT-60SA, achieved conditions in d-d experiments that would have reached the breakeven point had the plasma been d-t (which the JT-60 laboratory does not have the ability to handle). These will be superseded by ITER in the next decade. The main ICF experiment is NIF in the USA, which has achieved breakeven (measured in terms of fusion power over laser power) in one shot in December 2022; this shot also provided evidence for α-particle heating of the plasma. None of these facilities has the capability to be a practical electricity generator; all are purely research facilities. However, the proposed Korean K-DEMO project, aiming to start construc- tion in 2037, is intended to be a small-scale but fully-functional power station, capable of producing 500 MWe.

Tritium supply is a key issue in d-t fusion: it is currently produced in small quantities as a by-product of fission in CANDU heavy-water reactors, but they do not have the capacity to supply a full-fledged commercial fusion reactor (besides which, the aim of commercial fusion would be to replace fission!). A possible solution to this problem would be to “breed” tritium within the reactor, from 6Li(n,t)4He and/or 7Li(n,nt)4He. This idea will be tested at ITER.

To sum up, it is still true that practical fusion is 20 years away—but, this time, maybe it really is! How- ever, in the more than half a century since this prediction was first made, great strides have been made in renewable energy sources, particularly wind and solar power. Even if practical fusion power can be achieved, will it be able to compete with other forms of clean energy generation?