7. Nuclear Reactions#

Quick Links

From the Reading List

Nuclear reactions [Martin] Chapter 2.9

Nuclear reactions [Krane] Chapter 11

7.1. Reaction Kinematics#

So far we have concentrated on the properties of individual nuclei. However, in order to determine those properties, we must make use of nuclear reactions. Indeed, in order to have nuclei to study, and to exist to study them in the first place, we must have nuclear reactions: nuclear reactions build up the elements in stars, and the results of nuclear reactions tell us about nuclear structure.

7.1.1. Notation#

Particle physicists (and chemists) describe reactions by notation such as \(A + a \rightarrow B + b\). Nuclear physicists tend to use the more compact notation \(A(a,b)B\), where \(A\) is the target nucleus, struck by projectile a, which produces daughter nucleus \(B\) and ejectile \(b\). It is usual for \(A\) to be more massive than a, but it isn’t obligatory; there do exist facilities, such as GSI in Darmstadt, Germany, which produce beams of heavy ions, and when these are used it is possible for the projectile to be lighter than the target. The defining feature for the notation is that \(a\) is moving and \(A\) is stationary. In contrast, the products \(B\) and \(b\) will generally all be moving, owing to momentum transfer, so in this case \(B\) will typically be defined as the heaviest product (it’s also the one that is not measured: a typical nuclear experiment will measure the energy and angle of the ejectile(s) \(b\)).

It is possible for \(b\) to consist of more than one particle: for example, among the possible reactions listed in the JANIS nuclear database for neutrons striking an iron-56 target are \((n,2n)\), \((n,np)\) and \((n,2n+p)\). The ‘+’ sign may be omitted, e.g. \(^{27}\textnormal{Al}(p,3pn)^{22}\textnormal{Na}\).

There exist reactions for which this notation does not work well, such as fission (if a thermal neutron collides with a nucleus of 235U, the most likely outcome is that the nucleus will undergo fission, but the exact fission products can’t be predicted). There are conventions to handle these: for example, fission induced by a neutron would be described as \((n,\textnormal{fission})\) or \((n,f)\), and spallation reactions, where a fairly energetic projectile, usually a proton, strikes a heavy target and causes it to emit a large but not well-defined number of nucleons, can be described as \((p,\textnormal{spall})\). Both of these reaction types are interesting, fission for obvious reasons and spallation because it is used to produce neutrons for a wide range of research applications (and, in astrophysics, because it is responsible for the production of the light elements beryllium and boron).

7.1.2. Rutherford scattering#

Historically, the first use of nuclear reactions was the discovery of the atomic nucleus by Ernest Rutherford’s research group at Manchester University. They used the elastic scattering of alpha particles off metals.

At the time, the prevailing model of the atom was the “plum pudding”, in which the mass and positive charge of the atom are distributed over the whole atomic volume, with an appropriate number of electrons embedded in it. With such evenly distributed charge, alpha particles should simply pass through with only very minor deflection, but in fact some particles were deflected at large angles. Rutherford realised that this could be explained if the charge were actually concentrated in a small volume, and derived an expression for the resulting angular distribution.

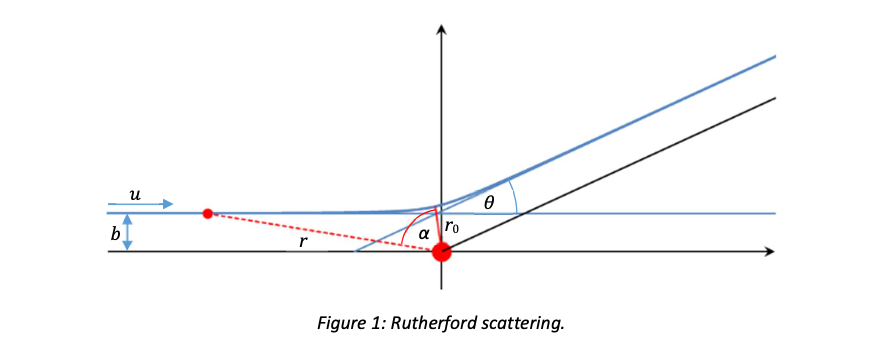

Consider an alpha particle incident on a nucleus with an impact parameter \(b\). The particle is seen to be scattered through an angle \(θ\) compared to its original direction. Because the scattering is elastic, the initial and final momenta of the particle have the same magnitude \(\mu\): only the direction changes. The final momentum is \(\mu(\cos θ, \sin θ) \), and the change in momentum \( Δ\vec{p} \) is \(\mu(\cos θ - 1, \sin θ) \) (since only two vectors are involved, this interaction all takes place in a single plane, so we can neglect the z component except at the very end).

The magnitude of \( Δ\vec{p} \) is

The direction of \( Δ\vec{p} \) is, by symmetry, along the line from the nucleus to the point of closest approach, labeled \( r_0 \) in figure 1. The Coulomb force in that direction when the particle is at a distance \(r\) from the nucleus is

where \(Ze\) is the charge on the nucleus, \(ze\) is the charge on the projectile, and the angle \(α\) is defined in figure 1.

Therefore, we have

To do the integral we need to find the relationships between the variables \(α\), \(r\) and \(t\). To do this, we use the fact that the Coulomb force is a central force (i.e. it is directed along the line joining the two charges), and therefore does not change the angular momentum. The initial angular momentum of the particle is \( \mu b \).

At any given time, we can write the instantaneous velocity of the particle as

where \( \hat{r} \) and \( \hat{α} \) are unit vectors in the radial and tangential directions. The angular momentum is then

since the component parallel to \( \vec{r} \) drops out in the vector product. This must be equal to \(\mu b\), so we have

We can substitute this into the integral to get

(For the limits, you can see from figure 1 that the total range of the angle \(α\) is \(\pi − \theta\), and it is negative to the left of \(𝑟_{0}\) and positive to the right; therefore it runs from \(−(\pi − \theta)/2\) to \(+(\pi − \theta)/2.\))

Solving this for b gives us

Now, if we have a uniform parallel beam of alpha particles with a flux per unit area \(Φ\), the flux with impact parameter between \(b\) and \(b + \textnormal{d}b\) is \(dΦ = 2\pi~b~\textnormal{d}b~Φ\). Differentiating the expression for \(b\) gives us

We now need to recognise that we are dealing with a three-dimensional experiment. The element of solid angle is \(\textnormal{d}Ω = \sinθ \textnormal{d}θ\textnormal{d}φ\). For a ring between \(θ\) and \(θ + \textnormal{d}θ\), we can integrate over φ to get \(\textnormal{d}Ω = 2π\sinθ \textnormal{d}θ = 4π\sin(θ/2)\cos(θ/2)\textnormal{d}θ\). This gives us

where \(\textnormal{d}f\) is the fraction of incoming alpha particles scattered over the angle between \(θ\) and \(θ + \textnormal{d}θ\) and \( K_\alpha = \frac{1}{2}\mu^2 \) is the kinetic energy of the incoming alpha particles.

This assumes a single nucleus. Obviously this is not the case: the number of nuclei per unit area is \(𝑛𝑥\) where \(𝑛\) is the number density of the material and \(𝑥\) is the thickness of the foil. From this derivation we expect that the number of alpha particles scattered through an angle \(θ\) will be proportional to:

the square of the atomic number of the target material;

the inverse fourth power of \(\sin(\theta/2)\);

the thickness of the foil (provided that the foil is thin—when it gets too thick all the alpha particles will simply stop within the foil);

the inverse square of the alpha particle kinetic energy.

Rutherford’s group (specifically, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden) conducted a series of experiments in 1913 that verified these predictions. This demonstrated that the atom contained an essentially pointlike nucleus.

Note

It is worth noting that you would obtain the same result if it were the negative charge of the atom that were concentrated in a small volume, i.e. if the electrons all clumped together in the midst of the distributed positive charge. Rutherford concluded that the nucleus was positively charged as a result of experiments using gas targets. This was consistent with the fact that the alpha particle was itself positively charged, and had earlier been identified by Rutherford with a fully ionised helium atom.

7.1.3. Kinematics#

7.1.3.1. The Q value#

Nuclear reactions are governed by \(E=mc^{2}\). The Q-value of a reaction is the difference in mass between the initial and final states, expressed as an energy (usually in MeV): for example, the Q-value of the reaction \(^{16}\textnormal{O}(p,α)^{13}\textnormal{N}\) can be calculated as follows (all numbers from Krane):

The nuclear mass of \(^{16}\textnormal{O}\) is

The mass of a proton is \(1.00727647 u\)

The nuclear mass of \(^{13}\textnormal{N}\) is

The mass of an α particle is \(4.00150618 u\).

Therefore the Q value is

\[ 16.997802u – 17.003405u = −0.005603 u = −5.219 \textnormal{MeV}. \]

A negative Q-value implies that the reaction will not proceed spontaneously, but will require the initial proton to contribute at least \(5.219\textnormal{MeV}\) of kinetic energy (actually, slightly more than this, because we need to allow for conservation of momentum). The minimum projectile kinetic energy required to make the reaction happen is called the threshold energy.

A positive Q-value means that the reaction will generate energy. However, this does not necessarily mean that the reaction has zero threshold in practice. Consider the reaction \(^{13}\textnormal{C}(α,n)^{16}\textnormal{O}\). This has Q-value \(2.216~\textnormal{MeV}\) (you should check this!). However, a zero-energy \(α\)-particle will not initiate the reaction, because Coulomb repulsion will ensure that it does not get close enough to the carbon nucleus to react with it. This imposes an effective threshold energy: it’s difficult to calculate exactly what it is, because quantum tunnelling ensures that the reaction will take place (with a reduced cross section) at energies lower than a classical calculation would suggest. This is what makes power generation by nuclear fusion so difficult: the relevant reactions do of course have positive Q (if they didn’t, they would not generate any energy!), but the kinetic energy required to overcome the Coulomb barrier means that the initial material has to be raised to an extremely high temperature for the fusion cross section to be high enough for useful energy output.

Reactions that have positive Q-values and an electrically neutral projectile (i.e. a neutron) will take place at arbitrarily low values of the neutron kinetic energy. In fact, it can be shown (see Krane section 12.4) that at low energies the neutron interaction cross section is proportional to \(1/v\), where \(v\) is the speed of the neutron (or, equivalently, to \(1/\sqrt{K_n}\), where \(K_n = \frac{1}{2}m_nv^2\) is the neutron kinetic energy).

This is why most designs of fission reactors moderate the neutrons produced in uranium fission, i.e. cause them to scatter repeatedly until they reach thermal equilibrium, corresponding to kinetic energies of around 0.025 eV—the cross section for subsequent capture by another \(^{235}U\) nucleus is about 500 times higher at this energy than it is at the \(O(1~\textnormal{MeV})\) energies at which they were originally emitted.

Elastic scattering, where the final state particles are the same as the initial state, obviously has \(Q = 0\) and zero threshold even for charged particles, since the projectile does not need to make contact with the target (see the derivation for Rutherford scattering above).

7.1.3.2. Reaction kinematics#

The projectile energies associated with nuclear reactions are typically a few MeV. At these energies protons, neutrons etc. are non-relativistic: the speed of a \(10~\textnormal{MeV}\) proton is about 14% of the speed of light. Therefore, unless we are dealing with electrons or photons, the kinematics of nuclear reactions can be handled using ordinary classical mechanics, and so we didn’t cover it in the lectures. However, being able to do kinematic calculations is an important part of nuclear physics, so we will go through a few examples (taken from Krane).

Scattering at angle θ Typically, we take some reaction \(A(a,b)B\) and measure the energy of the ejectile b at some angle \(θ\); we do not observe the daughter nucleus \(B\). Assuming that the target nucleus \(A\) is stationary, the kinematics of this are as follows:

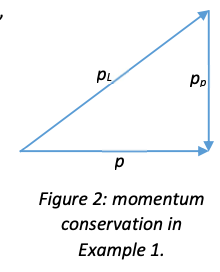

Conservation of momentum gives \( p^2_B = p^2_a + p^2_b - 2p_ap_b \cos θ \) (I’m not going to prove this, because it’s in one of the problems, but you should be able to work it out by looking at figure 2 below and considering what happens when the angle of the triangle is not 90°).

Conservation of energy gives \( K_a + Q = K_B + K_b \) (\(Q\) represents the energy consumed or released as a result of the total mass of the final state being, in general, different from the total mass of the initial state. If \( Q > 0 \), the released energy will add to the kinetic energies of the final-state particles; if \( Q < 0 \), some of the initial kinetic energy is converted to mass.)

We assume non-relativistic velocities, so for any particle \( K = \frac{p^2}{2m} \).

We want to eliminate \(K_B\), because we do not measure it. From energy conservation we find that

From momentum conservation

Equating these expressions gives

Collecting terms,

This is a quadratic in the unknown \( K_b \). Applying the usual quadratic formula (and cancelling off a factor of 2),

This looks hideous, but the key point is that everything on the right-hand side is known, so what it tells us is that a given angle \( \theta \) almost always corresponds to a specific ejectile kinetic energy \( K_b \), or — perhaps more usefully — that a given combination of \( K_b \) and \( \theta \) corresponds to a specific value of \( Q \). Therefore we can use scattering processes to explore the excited states of the nucleus B, even though we do not observe \(B\) itself.

Note

If \( Q < 0 \), for small \( K_a \) it is possible for the value of \( (m_b + m_B)((m_b - m_a)K_a + m_BQ) \) to be less than zero. In this case there will be two possible values of \( K_b^{1/2} \) corresponding to the two signs of the square root. This is normally relevant only for energies close to threshold—see Krane, figures 11.2(a) and (b).

7.1.3.3. Example 1#

In Coulomb scattering of 7.50 MeV protons by a target of \( ^7\textnormal{Li}\), what is the energy of protons at \(90°\) (i) if the scattering is elastic, (ii) if the \(^7\textnormal{Li} \) is left in its first excited state, 0.477 MeV above the ground state?

Answer First look up and/or calculate the relevant masses.

Atomic mass of \( ^7Li \) is 7.016003 u, so nuclear mass is

Mass of proton = \(1.00727647 u\).

Note

The initial proton has kinetic energy \( K \) and momentum \( p \). Scattered proton has kinetic energy \( K_p \) and momentum \( p_p \), and recoiling lithium nucleus has kinetic energy \( K_L \) and momentum \( p_L \).

As the proton mass is ~938 MeV/c², a proton with a kinetic energy of 7.50 MeV is not relativistic, so we can write kinetic energy as \( K = \frac{1}{2} mv^2 = \frac{p^2}{2m} \) where \( p \) is the momentum.

Part (i) In an elastic collision both kinetic energy and momentum are conserved. We have \( \vec{p} = \vec{p_p} + \vec{p_L} \). Drawing out the momentum sum (noting that this all takes place in the plane defined by the vectors \( \vec{p_p} \) and \( \vec{p_L} \), so it’s a two-dimensional problem), we see (figure 2) that \( p_L^2 = p^2 + p_p^2 \). Energy conservation gives \( K_p = K - K_L \), which we can write as

writing \( m \) for the proton mass and \( M \) for the lithium mass.

Substituting in for \( p_L^2 \) and cancelling the factor of 2,

Therefore

and dividing through by \( 2m \) gives us \( E_p = 0.74886E = 5.62~\textnormal{MeV} \).

Part (ii) In the second case, momentum is conserved as before, but the energy conservation equation is now

where \( \Delta E = 0.477 \textnormal{MeV}\) is the excitation energy.

Therefore we have

Putting in the numbers gives

Notice that in an actual experiment, if we observe protons at 90° to the original direction, we will see a peak at \( E_p = 5.62~\textnormal{MeV}\) corresponding to elastic scattering, and a peak at \(5.20~\textnormal{MeV}\) corresponding to the first excited state (plus more peaks at lower energies corresponding to higher excited states). We could then work this equation backwards to extract \( \Delta E \) from the known \( E_p \).

Also note that we could have done this question using the general expression for \( K_b^{1/2} \) that we derived earlier. You should check that this gives you the same answers.

7.1.3.4. Example 2#

Calculate the Q value of the reaction \( p + ^4\textnormal{He} \rightarrow ^1\textnormal{H} + ^3\textnormal{He} \). What is the threshold energy (i) for protons incident on helium and (ii) for \( \alpha \) particles incident on hydrogen?

Answer (Note that in this case we couldn’t use the bracket notation for the reaction, because we are asked to look at two different cases, \( ^4\textnormal{He}(p,d)^3\textnormal{He} \) and \( ^1\textnormal{H}(\alpha,d)^3\textnormal{He} \).)

The relevant masses are, from Krane: proton \(1.00727647~u\), \(α\) particle \(4.00150618~u\), deuteron \(2.01355321~u\), \(^3\textnormal{He}\) nucleus \(3.014932~u\).

The Q value is therefore \(-0.019702~u = -18.353 \textnormal{MeV}\) (rounding everything to 6 decimal places in \(u\) so as to match the precision of the mass of \(^3\textnormal{He}\): Krane only gives atomic masses to 6 decimal places).

To calculate the threshold energies, we use the equation for \( K_b^{1/2} \) we derived above. This only describes a physically possible reaction if it has a real solution (obviously observed kinetic energies are not complex numbers), and it only has a real solution if the term inside the square root is non-negative. The limiting case is when the argument of the square root is exactly zero,

Furthermore, for the absolute minimum possible value of \( K_a \) we must have \( \theta = 0 \): we do not want to waste energy giving the products transverse momentum. Therefore \( \cos \theta = 1 \) and we have

This simplifies to

If \( Q > 0 \), this is never true (except in the case where \( m_a > m_b + m_B \), in which case our assumption of non-relativistic velocities is unlikely to be right). This is not surprising, because if \( Q > 0 \) there should not be a kinematic threshold: the reaction releases energy. However, in the case we are dealing with, \( Q < 0 \), and we have:

(i) \( K_p = 18.353 \frac{5.028485}{5.028485 - 1.007276} = 22.950~\textnormal{MeV} \)

(ii) \( K_a = 18.353 \frac{5.028485}{5.028485 - 4.001506} = 89.863~\textnormal{MeV}\).

The reason that the threshold for the alpha-induced reaction is so much higher is that \( p = \sqrt{2mK} \): for a given energy, the alpha particle has a much higher momentum than the proton, and therefore more of the initial kinetic energy is required for momentum conservation and so is not available to convert into mass. However, the energy per nucleon is very similar for the two cases, \(23.0~\textnormal{MeV}\) for (i) and \(22.5~\textnormal{MeV}\) for (ii); for this reason, projectile energies are often specified as energy per nucleon, \( K/A_p \), where \( A_p \) is the mass number of the projectile, rather than total energy.

Notice that \(23~\textnormal{MeV}\) \( \ll 938.3 MeV/c^2 \) and \(90~\textnormal{MeV}\) \( \ll 1876 MeV/c^2 \), so the assumption that everything is non-relativistic is reasonably safe (though not safe to 5 significant figures—we should really round our answers to \(23.0\) and \(89.9~\textnormal{MeV}\)). This should always be checked: if you end up with a kinetic energy which is not much less than the mass, you need to redo the kinematics using relativistic expressions, as you did in the particle physics course.

7.1.3.5. Example 3#

In the reaction \( ^9Be(\alpha,n)^{12}C \), find the maximum and minimum neutron energies when the incident α energy is (i) 7.0 MeV and (ii) 1.0 MeV.

Answer The relevant masses are:

\( ^9\textnormal{Be}: 9.012182 - 4(0.00054858) = 9.009988 u \)

\(α: 4.001506 u\)

\(n: 1.008665 u\)

\( ^{12}\textnormal{C} \): \(12u\) (by definition) – \(6(0.00054858) = 11.996709 u\).

The \(Q\) value is \(0.006120 u = 5.701\) MeV.

The maximum neutron energy will occur when \(θ = 0\) (the neutron is emitted in the same direction as the incident \(α\)), and the minimum neutron energy will be when \(θ = π\).

The simplest way to do this is to apply the equation for \( K_{b}^{1/2} \). For \(\cos\theta = 1\) we have

Notice that the argument of the square root is always larger than \( m_a m_n K_a \), so only the positive sign is relevant (kinetic energies cannot be negative).

For \(\cos θ = –1\) all that happens is that the first term changes sign, so we have

Putting in the numbers gives:

(i) \( K_{n,max} = 12.4 MeV; K_{n,min} = 7.3~\textnormal{MeV}; \)

(ii) \( K_{n,max} = 6.7 MeV; K_{n,min} = 5.2~\textnormal{MeV}. \)

(All answers rounded to the nearest $0.1~\textnormal{MeV}, to match input precision; arguably we should round 12.4 to 12, but as the first figure is a 1 it is not unreasonable to keep an extra figure here.)

Note

It is worth noting here that the units of the mass cancel out, so provided that all masses are expressed in the same units (don’t put some of them in u and others in MeV/c²…) you do not have to convert them to SI or MeV or anything else.

7.1.3.6. Reaction Kinematics Summary#

All the above examples assume a two-body final state, i.e. \(b\) is one particle. If this is the case, the reaction kinematics can be determined up to one angle, \(θ\), that appears in the equations and one, \(φ\), that is irrelevant (the final state can be rotated through any angle around the direction of the projectile a without affecting the kinematics). If \(b\) consists of more than one particle, the kinematics are no longer uniquely determined (cf. the electron energy distribution in beta decay); however, threshold energy and minimum and maximum energies can still be calculated.

In the examples, I have used the standard nuclear physics approach of assuming that the speeds involved are non-relativistic. This is OK to about the \(1%\) level. It is, of course, also possible to do all these calculations using relativistic kinematics, as you did in the particle physics course last semester. Relativistic kinematics must be used if the projectile is an electron—MeV energies imply \(v ≈ c\) for an electron.

7.1.4. Types of Reaction#

Besides Coulomb scattering, in which there is no real contact between the charged projectile and the target nucleus, there are two main types of nuclear reaction:

direct reactions, in which the projectile interacts with a small number (usually one) of nucleons on the surface of the target nucleus (a peripheral reaction);

compound-nucleus reactions, in which the projectile combines with the target to form an excited compound nucleus, which then de-excites to produce the daughter nucleus and ejectile(s).

These types of reaction are not mutually exclusive: for example, an elastic scattering reaction such as (p,p) [the notation (p,p) means that the proton is deflected, but does not lose any energy; in contrast, (p,p’) denotes an inelastic collision where the proton loses energy by exciting the target] could take place by Coulomb scattering (no contact between projectile and target), direct reaction (proton hits a nucleon on the surface of the target and is deflected) or compound-nucleus reaction (proton and target combine, but the resulting compound nucleus happens to de-excite by emitting a proton—this is not very likely, but could happen if the target were already quite proton-rich). In general, direct and compound-nucleus reactions can be distinguished by the angular distribution of the ejectile: in direct reactions, not much of the initial momentum is transferred to the target, and the ejectile(s) tend to travel in the same direction as the incoming projectile, i.e. the angular distribution is forward-peaked (even when transformed to the centre of mass frame). In contrast, the de-excitation of the compound nucleus is a separate process from its initial formation, and therefore the angular distribution of the decay products tends to be fairly isotropic.

7.2. Direct Reactions#

7.2.1. Characteristics of direct reactions#

The fundamental characteristic of direct reactions is that they take place in the time it would take the projectile to traverse the nucleus. There are various ways of estimating this, but they all boil down to a simple calculation: the speed of a few-MeV nucleon is of order \(0.1c\); the size of a typical target nucleus is a few femtometres; \(10^{-15}/10^{7} = 10^{-22}\), so a direct reaction should take place on a timescale of order \(10^{-22}~\textnormal{s}\). The logic of this is that if the reaction is over in the time it would have taken the projectile to cross the nucleus, there has not been time for a compound nucleus to form, so it can’t be a compound-nucleus reaction.

Note

This is an order-of-magnitude estimate: it doesn’t have to be precise. We will see later that the timescale for compound-nucleus reactions is much longer.

Direct reactions tend to involve relatively high-energy projectiles. The reason for this is that a low-energy projectile, such as a thermal neutron with an energy of \(0.025~\textnormal{eV}\), has a de Broglie wavelength which is much larger than an individual nucleon: it will “see” the nucleus as an undifferentiated blob, so it is unlikely to interact with individual nucleons. In contrast, a \(100~\textnormal{MeV}\) nucleon would have a de Broglie wavelength of the same order as the diameter of a proton and would be much more likely to undergo a direct reaction.

As noted earlier, the products of direct reactions are strongly forward-peaked, because not much of the incoming energy is transferred to the target nucleus.

7.2.2. Types of direct reaction#

Because direct reactions involve only a few nucleons near the surface of the target nucleus, the possible reactions are rather limited—for example, it would not be possible to induce fission by a direct reaction. The principal types are:

elastic and inelastic scattering—the ejectile is identical to the projectile, with the same kinetic energy (elastic) or reduced kinetic energy (inelastic);

charge exchange—as the name indicates, reactions in which charge is exchanged between projectile and target, most obviously \((n,p)\) and \((p,n)\), but also \(^3\textnormal{He},^3\textnormal{H}\) or vice versa;

transfer reactions—a nucleon (occasionally more than one) is transferred from projectile to target:

stripping reaction—transfer is from projectile to target, e.g. \((d,p)\) or \((d,n)\);

pick-up reaction—transfer is from target to projectile, e.g. \((p,d)\); knock-out reactions—a nucleon or light cluster (e.g. a particle) is knocked out of the target but not attached to the projectile, e.g. \((n,2n)\).

All of these can also take place via the compound-nucleus route. The direct reaction will dominate at high projectile energies and in the forward direction. Because direct reactions, despite the use of high-energy projectiles, only involve small energy transfers, they tend to populate low-level excited states, whereas compound-nucleus reactions typically involve higher levels of excitation (for a given projectile energy). Consequently, it is usually possible to disentangle the direct reaction contribution from the compound-nucleus route without too much ambiguity.

7.2.3. Applications of direct reactions#

A key feature of direct reactions is that they tend to be very simple, since only a few nucleons are involved. This makes them easy to analyse theoretically, so they are extremely useful in understanding nuclear structure.

Since only a small fraction of the incident projectile energy is transferred in direct reactions, the cross section as a function of incident particle energy is smooth. The interesting observables are the energy and angular distributions of the ejected particle(s).

7.2.4. Elastic scattering and the optical model#

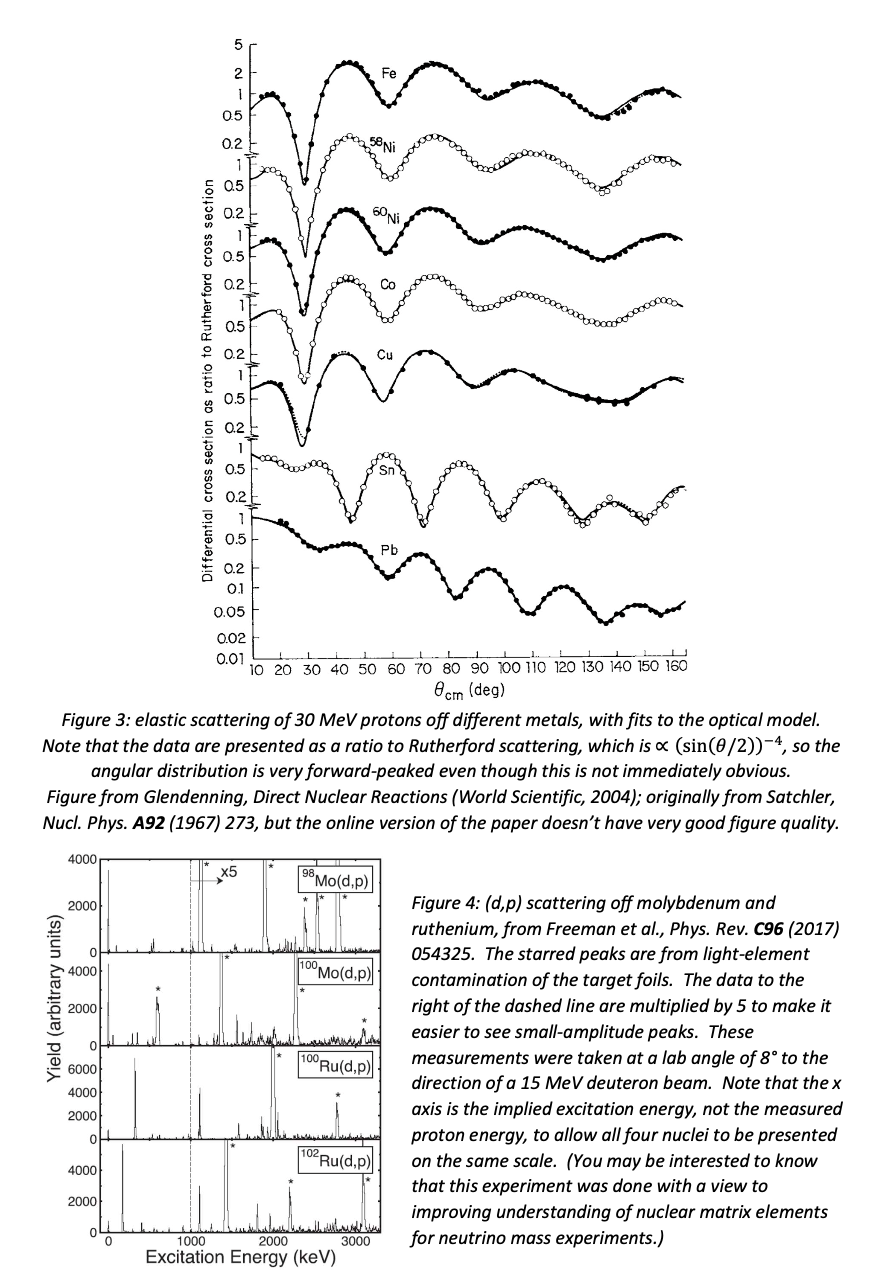

Elastic scattering of a projectile by a target nucleus is analogous to diffraction of light around an obstacle, and similar diffraction patterns are observed. These are described using the optical model, which essentially treats the projectile as moving in a potential generated by the nucleons in the nucleus. The nucleus is not opaque to projectiles, so the diffraction minima do not go down to zero (this is sometimes referred to as the “cloudy crystal ball model”).

The potential used in the optical model takes into account the nuclear potential, the Coulomb potential (for charged projectiles), spin-orbit interactions, potentially non-spherical shapes, etc. It is in general complex: the imaginary part is there to account for projectiles that do not scatter elastically. The description of the data can be extremely good (see figure 3); it is usually better for simple projectiles such as protons and neutrons than for more complicated objects.

Fitting optical model parameters gives nuclear physicists information about the size, shape and spin of the target nucleus, which means that direct nuclear reactions are an important probe of overall nuclear properties.

7.2.5. Direct reactions and excited states#

In compound-nucleus reactions, as we will see later, excited states of the compound nucleus can be observed as resonances in the cross section: it is more likely that the projectile will merge with the target nucleus if the total centre-of-mass energy corresponds to an excited state. This does not happen in direct reactions, because the projectile does not transfer all its energy to the target. However, as we saw earlier, if the final state contains only a single ejectile, the Q-value of the reaction can be deduced from the energy and angle of the ejectile, and hence excited states will cause peaks in the ejectile energy spectrum as measured at a specific scattering angle. The heights of the peaks can be used to deduce information about the spin of the state. The \((d,p)\) stripping reaction and its inverse, the \((p,d)\) pickup reaction, have historically been extremely important in such studies. Figure 4 shows results from a recent \((d,p)\) experiment on molybdenum and ruthenium isotopes.